Introduction

In-game advertising, or IGA, is getting to be a potent buzzword in our industry. It also elicits some strong connotations - things like corporate greed, spyware and spam. Each gamer reacts differently to the ideas, but almost all fit into two camps - those who detest it to the point of not buying the games that contain it, and those who recognize it as an unfortunate reality and are willing to bear with some of it.Love it or hate it, the truth is that IGA is here to stay. But before we go crying in our beers and throwing our tea into the virtual harbour, maybe we need to take a look at what IGA really is - what it has been, what it is now, and what it could be. Along the way, we'll even discuss some of the business behind it, and why it maybe isn't the villain we as gamers have made it out to be.

So let's put a penny in the machine and take a look, shall we? Oh, and don't forget to buy something from our bit-tech IGA gift store on the way out!

A little history...

For as much as IGA has been recently thrust into the spotlight with front-page titles like Battlefield: 2142, the reality is that the concept is frankly not new at all. In fact, the most new thing about it is having agencies devoted to it, which maybe should make gamers rejoice. After all, we've always been crying that we're not publicly respected or acknowledged as having any real social worth - what greater worth is there than for people to spend millions of dollars for two seconds of your viewing time?But anyhow, back to history. Have you ever wondered how long the concept of in-game advertising has been a reality? Well, technically that depends on the definition of "advertise." So for a brief second, we'll consult our dear friends at Oxford:

" • verb 1 present or describe (a product, service, or event) in a public medium so as to promote sales. 2 seek to fill (a vacancy) by placing a notice in a newspaper or other medium. 3 make (a quality or fact) known."

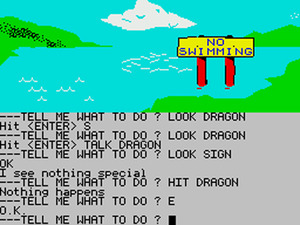

So even by the worst of definitions, advertising is putting forth any product, service, or event publicly. So, for instance, a game designer coding references and highlights of previous or upcoming titles would qualify as in-game advertising... and that is exactly what happened, all the way back in 1978 with Scott Adams' (not to be confused with the Dilbert creator) text-based Adventureland. In it, he coded an advertisement for his next upcoming game, Pirate Adventure!.

Left - the text-based Adventureland. Right - Chupa chups candy sponsored Zool

What, you were looking for something more blatant? The reality is that it often isn't that blatant. Each time a publisher sneaks in some references to other games, or a developer mentions previous or future titles, it's a plug - in-game advertising is nothing new, we just mistake it as story arc.

For those of you interested in more direct and noticeable forms, they're certainly present. For instance, in 1992 the candy company Chupa Chups sponsored its logo throughout the platformer Zool, a popular British side-scroller that ran on many platforms including the GameBoy and SNES. The brand name and a couple products appeared in various spots throughout the game, including a whole bonus section in the "sweets" world.

Left - Gran Turismo featured over 100 authentic cars. Right - Michael Jackson's Moonwalker

Of course, some advertising just fits to the point that it's noticeable when it doesn't exist. For instance, what is a sports game without a sport clothing company's logo? Along with relativity serious sporting titles like FIFA and Madden, racing games will often feel absent without some type of brand recognition. Adverts certainly exist in the stadiums and tracks themselves, and their absence in a game makes it feel lacking. In order to combat this, publishers will often smear their own logos over spaces where advertisers wouldn't pay to play.

Gran Turismo featured over 100 licensed cars, and that didn't even include the parts or the billboards. Of course, that was with a catch - the game was not permitted to display "car damage" as a request by the manufacturers. Apparently, the companies didn't find it to be nearly as good of advertising to watch how realistically their vehicles could disintegrate on the track.

One of the most inventive and insidious forms of IGA, though, happens to be the games devoted to the advertisement itself. Though many great franchises like Spiderman and X-men fall into this category, the biggest nod has to go to the music genre. It started with Michael Jackson's Moonwalker, a game devoted to the self-proclaimed King of Pop himself, but it ended very, very far away. You need only pick up a game of Dance Dance Revolution or Guitar Hero to see licensing at its finest, and there the publisher actually pays the RIAA to advertise its bands.

MSI MPG Velox 100R Chassis Review

October 14 2021 | 15:04

Want to comment? Please log in.