How Games Tell Stories

Back in 2005 America’s leading film critic Roger Ebert weighed in on the state of modern video games, saying:“Video games [are] inherently inferior to film and literature. There is a structural reason for that: Video games by their nature require player choices, which is the opposite of the strategy of serious film and literature, which requires authorial control.”

Needless to say not everyone agreed. Ebert's criticism provoked impassioned responses and the man got ravaged by the internet community, with such diverse voices as Clive Barker rallying against him. Clive said:

"This is a medium that's barely two decades old, and he (Ebert) is saying oh, there's no War And Peace yet — of course there isn't! ... We can debate what art is, we can debate it forever. But if the experience moves you, some way or another, even if it just moves your bowels, I think it's worthy of some serious study... Games mean something to a lot of people."

Unlike many criticisms of games though - those tabloid headlines that slam them as vicious, violent, stupid and corrupting - Ebert's makes sense. It's logical. It's correct. Or at least it seems to be - games, after all, appear to involve player choices, and movies don't appear to.

Ebert isn’t entirely alone in his viewpoint; a similar feeling spreads right through to your friendly, neighbourhood game designer circles – some of the people you’d most expect to lecture on the strengths of games as a storytelling device are actually thinking the opposite. Speaking with Braid designer Jonathan Blow, he describes this basic dilemma:

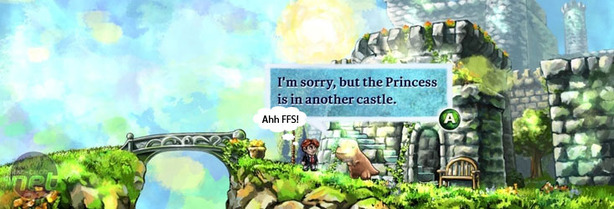

“A lot of players want strong narrative in games. The question, though, is whether that is ever going to work, in the sense of the narrative being as strong as what you can get in a great novel or a great film.”

“I personally don't think it will work. The basic idea of gameplay conflicts too much with the techniques of strong storytelling.”

What’s interesting here is that Ebert and Blow are describing two sides of the same sort of coin. Where Ebert says gameplay prevents games from moving forward as a narrative art, Blow argues it transforms them into an entirely different animal. It's a refreshing change when you consider that for years developers, game journalists and PRs have used cinema in particular as a reference point for directing stories in a visual medium, using cut scenes and the like to convey plot. That’s why every developer and his brother claims that their game is the most ‘cinematic’.

The question is do we, as gamers, limit ourselves by comparing games to the stories and structure of films and novels, by wanting a game equivalent of War & Peace or Citizen Kane? Are video games even storytelling systems in the same sense as novels or cinema? Can a story exist that's told in different way to the three-act, narrated structure of books and films? And does anybody expect the Spanish Inquisition?

MSI MPG Velox 100R Chassis Review

October 14 2021 | 15:04

Want to comment? Please log in.