Google Transparency Report points to increasing censorship

June 18, 2012 | 11:26

Companies: #google #microsoft #riaa

Google has released an update to its regular Transparency Report which suggests government removal requests for political speech are at an all-time high, with the US having doubled its content removal requests since the last report.

Google's Transparency Report publishes official requests received to remove content, whether that content is hosted on a Google service - videos on YouTube, posts on Google+, photographs on Picasa and the like - or simply linked through from Google's search engine. It provides a handy insight into the attitudes of various world governments to free speech - and, given the UK's steady march towards total government oversight on all forms of communication, a timely reminder of the battle between free speech and government censorship.

'Unfortunately, what we’ve seen over the past couple years has been troubling, and today is no different,' Dorothy Chou, senior policy analyst at Google, writes of the latest report. 'When we started releasing this data in 2010, we also added annotations with some of the more interesting stories behind the numbers. We noticed that government agencies from different countries would sometimes ask us to remove political content that our users had posted on our services. We hoped this was an aberration. But now we know it's not.

'This is the fifth data set that we've released. And just like every other time before, we've been asked to take down political speech. It's alarming not only because free expression is at risk, but because some of these requests come from countries you might not suspect—Western democracies not typically associated with censorship. For example, in the second half of last year, Spanish regulators asked us to remove 270 search results that linked to blogs and articles in newspapers referencing individuals and public figures, including mayors and public prosecutors. In Poland, we received a request from a public institution to remove links to a site that criticised it. We didn't comply with either of these requests.'

Google's annotations for the US make sombre reading: between July and December 2011, US agencies made 103 per cent more content removal requests than in the previous period. These requests included a demand to remove blog content which 'allegedly defamed a law enforcement official in a personal capacity,' and another from a local law enforcement agency to remove 1,400 YouTube videos for alleged harassment. Neither requests were satisfied.

Additional US requests include five user accounts containing threatening or harassing content - four of which were removed, resulting in the deletion of 300 videos from YouTube - and a court order demanding 218 search results linking to allegedly defamatory websites be removed, of which 25 per cent were.

In the UK, the Association of Police Officers demand the removal of five user accounts which allegedly promoted terrorism. These accounts were found to be in violation of YouTube's Community Guidelines - although Google doesn't specify which part - and terminated, with the removal of 640 videos from the service.

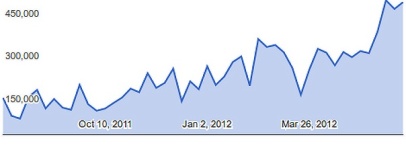

Google's Transparency Report also provides a fascinating insight into the world of copyright. According to the company's copyright takedown report, Google has received almost two million URLs for removal from search results in the last two months alone for reasons of alleged copyright infringement. The list of rights holders makes for interesting reading: of the reported URLs, 448,236 linked to content believed to infringe Microsoft's copyrights; a further 217,449 to content belonging to US broadcaster NBC.

Those who demonise the Recording Industry Association of America (RIAA) may be interested in the next little fact: while RIAA members accounted for 77,767 of the URL take-down demands, UK equivalent the British Phonographic Industry (BPI) far outstretched it with a whopping 150,063 URLs - making it the second largest source of take-down requests for copyright infringement, behind Microsoft representative Marketly LLC.

'We realise that the numbers we share can only provide a small window into what's happening on the Web at large,' concludes Chou, 'but we do hope that by being transparent about these government requests, we can continue to contribute to the public debate about how government behaviours are shaping our Web.'

Google's Transparency Report publishes official requests received to remove content, whether that content is hosted on a Google service - videos on YouTube, posts on Google+, photographs on Picasa and the like - or simply linked through from Google's search engine. It provides a handy insight into the attitudes of various world governments to free speech - and, given the UK's steady march towards total government oversight on all forms of communication, a timely reminder of the battle between free speech and government censorship.

'Unfortunately, what we’ve seen over the past couple years has been troubling, and today is no different,' Dorothy Chou, senior policy analyst at Google, writes of the latest report. 'When we started releasing this data in 2010, we also added annotations with some of the more interesting stories behind the numbers. We noticed that government agencies from different countries would sometimes ask us to remove political content that our users had posted on our services. We hoped this was an aberration. But now we know it's not.

'This is the fifth data set that we've released. And just like every other time before, we've been asked to take down political speech. It's alarming not only because free expression is at risk, but because some of these requests come from countries you might not suspect—Western democracies not typically associated with censorship. For example, in the second half of last year, Spanish regulators asked us to remove 270 search results that linked to blogs and articles in newspapers referencing individuals and public figures, including mayors and public prosecutors. In Poland, we received a request from a public institution to remove links to a site that criticised it. We didn't comply with either of these requests.'

Google's annotations for the US make sombre reading: between July and December 2011, US agencies made 103 per cent more content removal requests than in the previous period. These requests included a demand to remove blog content which 'allegedly defamed a law enforcement official in a personal capacity,' and another from a local law enforcement agency to remove 1,400 YouTube videos for alleged harassment. Neither requests were satisfied.

Additional US requests include five user accounts containing threatening or harassing content - four of which were removed, resulting in the deletion of 300 videos from YouTube - and a court order demanding 218 search results linking to allegedly defamatory websites be removed, of which 25 per cent were.

In the UK, the Association of Police Officers demand the removal of five user accounts which allegedly promoted terrorism. These accounts were found to be in violation of YouTube's Community Guidelines - although Google doesn't specify which part - and terminated, with the removal of 640 videos from the service.

Google's Transparency Report also provides a fascinating insight into the world of copyright. According to the company's copyright takedown report, Google has received almost two million URLs for removal from search results in the last two months alone for reasons of alleged copyright infringement. The list of rights holders makes for interesting reading: of the reported URLs, 448,236 linked to content believed to infringe Microsoft's copyrights; a further 217,449 to content belonging to US broadcaster NBC.

Those who demonise the Recording Industry Association of America (RIAA) may be interested in the next little fact: while RIAA members accounted for 77,767 of the URL take-down demands, UK equivalent the British Phonographic Industry (BPI) far outstretched it with a whopping 150,063 URLs - making it the second largest source of take-down requests for copyright infringement, behind Microsoft representative Marketly LLC.

'We realise that the numbers we share can only provide a small window into what's happening on the Web at large,' concludes Chou, 'but we do hope that by being transparent about these government requests, we can continue to contribute to the public debate about how government behaviours are shaping our Web.'

MSI MPG Velox 100R Chassis Review

October 14 2021 | 15:04

Want to comment? Please log in.