Panasonic has announced that it has become the first company to begin mass production of computing devices featuring non-volatile ReRAM components.

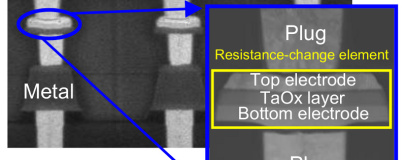

One of several technologies claimed to represent the future of computing, ReRAM - Resistive, or Resistance, Random Access Memory - is a high-speed non-volatile storage medium which uses resistance, rather than voltage or magnetism, to store data. The result is a flash-like memory which offers performance near to that of traditional Dynamic RAM (DRAM) components - blurring the lines between mass storage and RAM, protecting data in the event of a power outage, and reducing the power required by a memory module significantly.

Previous efforts in the commercialisation of ReRAM - including a prototype module from Elpida and a hybrid SSD offering eleven-fold speed improvements - have been hampered by the complexity of its manufacture. It wasn't until May last year that researchers were able to produce a cheap room-temperature ReRAM device using simple and affordable manufacturing methods.

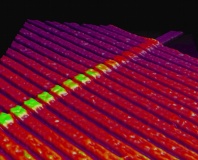

Now, Panasonic is taking ReRAM into the mass market with the news that it has become the first company to begin mass production of a product based around the technology. Dubbed the MN101LR series, the microcomputers are being produced from August at a rate of a million units per month using the company's newly-developed 0.18µm ReRAM modules.

Before you get too excited, however, it's worth checking the specifications of the MN101LR devices. Designed for embedded use, the systems are eight-bit microcomputers running at 10MHz with just a few kilobytes of ReRAM available to the user. The target market, Panasonic explains, is low-complexity systems such as battery-powered healthcare products, security systems, automotive and sensor devices.

Even in this market segment, ReRAM promises much: compared to the flash-based MN101E microcomputer it replaces, the new devices boast a 50 per cent reduction in power draw and a ten-fold boost in longevity while also increasing the throughput capabilities of the processor.

Clearly, while there's quite some way to go before ReRAM scales up to threaten traditional flash or DRAM in desktop or laptop computers, the technology is already proving itself worth of the effort researchers have put in thus far.

One of several technologies claimed to represent the future of computing, ReRAM - Resistive, or Resistance, Random Access Memory - is a high-speed non-volatile storage medium which uses resistance, rather than voltage or magnetism, to store data. The result is a flash-like memory which offers performance near to that of traditional Dynamic RAM (DRAM) components - blurring the lines between mass storage and RAM, protecting data in the event of a power outage, and reducing the power required by a memory module significantly.

Previous efforts in the commercialisation of ReRAM - including a prototype module from Elpida and a hybrid SSD offering eleven-fold speed improvements - have been hampered by the complexity of its manufacture. It wasn't until May last year that researchers were able to produce a cheap room-temperature ReRAM device using simple and affordable manufacturing methods.

Now, Panasonic is taking ReRAM into the mass market with the news that it has become the first company to begin mass production of a product based around the technology. Dubbed the MN101LR series, the microcomputers are being produced from August at a rate of a million units per month using the company's newly-developed 0.18µm ReRAM modules.

Before you get too excited, however, it's worth checking the specifications of the MN101LR devices. Designed for embedded use, the systems are eight-bit microcomputers running at 10MHz with just a few kilobytes of ReRAM available to the user. The target market, Panasonic explains, is low-complexity systems such as battery-powered healthcare products, security systems, automotive and sensor devices.

Even in this market segment, ReRAM promises much: compared to the flash-based MN101E microcomputer it replaces, the new devices boast a 50 per cent reduction in power draw and a ten-fold boost in longevity while also increasing the throughput capabilities of the processor.

Clearly, while there's quite some way to go before ReRAM scales up to threaten traditional flash or DRAM in desktop or laptop computers, the technology is already proving itself worth of the effort researchers have put in thus far.

MSI MPG Velox 100R Chassis Review

October 14 2021 | 15:04

Want to comment? Please log in.