The games industry needs to learn when to let things end

July 6, 2017 | 14:00

Companies: #activision #bioware #cd-projekt #ea #ubisoft

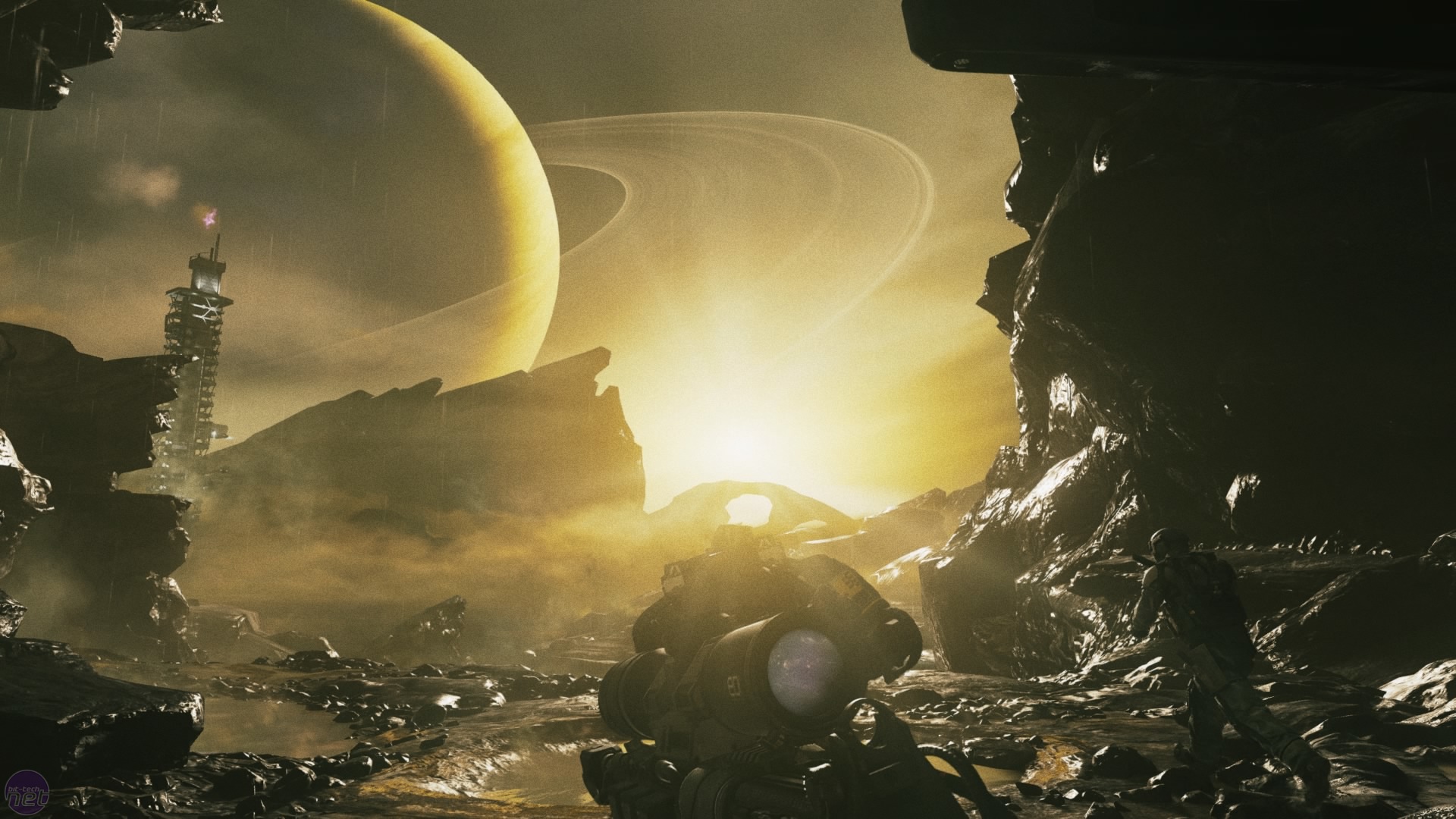

When reports circulated this week that BioWare has cancelled Mass Effect: Andromeda’s DLC and dropped ideas for a potential sequel, I was sad. It’s never pleasant to see a game fail (unless it’s really terrible, in which case it can be quite amusing), especially when it’s from a studio that does as much good work as BioWare. But I also felt an overriding sense that none of this needed to happen at all.

Mass Effect

was done. It was over, finished. The Genophage had been cured, the war between

the Geth and the Quarians resolved, Shepard’s quest to save humanity ended (if

not to everyone’s satisfaction). We’d enjoyed three forty-hour RPGs in which

BioWare had explored its concept more thoroughly than most artists ever get

the chance to. Two of those RPGs are amongst the best I’ve ever played.

Mass Effect

was more done, more finished, more over than any other franchise in gaming. But

nothing is done in the games industry so long as there’s money to be made, and as

a result we’ve got a fourth Mass Effect. Andromeda isn’t terrible, not quite.

But it’s a long, long way from the highs of Mass Effect 2 and the best bits of

3, a turgid, confused mess of a game that wants to be too many things and fails

to excel at any of them. Consequently, instead of having a nice, neatly tied

off trilogy of games, we’ve got this malformed, abortive start to a new trilogy

hanging out like a builder’s arse.

Mass Effect

was more done, more finished, more over than any other franchise in gaming. But

nothing is done in the games industry so long as there’s money to be made, and as

a result we’ve got a fourth Mass Effect. Andromeda isn’t terrible, not quite.

But it’s a long, long way from the highs of Mass Effect 2 and the best bits of

3, a turgid, confused mess of a game that wants to be too many things and fails

to excel at any of them. Consequently, instead of having a nice, neatly tied

off trilogy of games, we’ve got this malformed, abortive start to a new trilogy

hanging out like a builder’s arse.

The games industry does this all the time, working and working and working an IP until it dies of exhaustion, pulling a franchise out of retirement and exposing all its old and wrinkly mechanics to an audience that no longer cares. EA has done it with Mass Effect, Ubisoft flogged the Assassin’s Creed horse so much it had to give it a year off so the wounds could heal. Activision is the worst; Call of Duty is so conceptually bankrupt it’s gone back in time for new ideas, while the company also killed Guitar Hero so dead it took most of the peripherals market with it.

The games

industry’s fondness for sequels is well documented, but it’s just because the big

publishers are greedy and risk-averse. Games are driven by play, by the

interaction between the player and the systems created by the developer. Often

it isn’t possible for a developer to explore a mechanical concept completely

the first time around. Or perhaps the team only realise what else they could have

done with an idea once a game is on the market.

The games

industry’s fondness for sequels is well documented, but it’s just because the big

publishers are greedy and risk-averse. Games are driven by play, by the

interaction between the player and the systems created by the developer. Often

it isn’t possible for a developer to explore a mechanical concept completely

the first time around. Or perhaps the team only realise what else they could have

done with an idea once a game is on the market.

Game

development is grounded in iteration, and sometimes that iteration stretches

beyond a single project. Such iteration has resulted in some of the best games

around. Mass Effect 2 was superb precisely because BioWare doubled-down on what

worked in the first game and either improved or cut out the stuff that didn’t.

Then there are games like The Witcher 3, which CD Projekt slowly built towards

over the course of eight years and three games. The result was perhaps the

finest fantasy RPG ever made.

Game sequels

are produced for the more typical reasons too, such as continuing a story a-la

Mass Effect, or creating a new adventure for a well-liked character, such as

with Mario or Zelda. But even with these games, developers prioritise

mechanical iteration and innovation. Indeed, Nintendo tends to frame its games

around a new mechanical concept. It comes up with an idea it wants to

explore and constructs the game around that. This is why its games are

so consistently strong, despite basically telling the same story over and over.

Game sequels

are produced for the more typical reasons too, such as continuing a story a-la

Mass Effect, or creating a new adventure for a well-liked character, such as

with Mario or Zelda. But even with these games, developers prioritise

mechanical iteration and innovation. Indeed, Nintendo tends to frame its games

around a new mechanical concept. It comes up with an idea it wants to

explore and constructs the game around that. This is why its games are

so consistently strong, despite basically telling the same story over and over.

Sequels exist because developers haven’t always stopped exploring an idea when a story concludes. But problems arise when the games industry priorities the making of a sequel over the exploration of a concept. This is why the mainstream industry’s current obsession with annual releases is so creatively toxic, as it forces design and creativity into a strict schedule and reduces developers to ploughing ahead with a project regardless of whether they’ve got any good ideas or not. The results are backwards-looking games such as Assassin’s Creed Unity or inconsistent games like Andromeda. It doesn’t matter how efficient your assembly line is, you can’t get inspiration off a conveyor belt.

When you’re

cranking out sequels simply to keep to a schedule, you’re only going to damage

the long-term credibility of the series in question. Now when I think about

Mass Effect, instead of my brain saying, 'Yeah, that was a great series,' now it

also adds, 'Shame about Andromeda.' As for Assassin’s Creed, its ludicrous

number of sequels is the first thing I think about; it’s what the series has

become known for. This might not

matter to company executives in the short term, but when the money dries up and

a legacy is all a game has left, it matters a whole lot more. It also matters

if you do have a good idea for a

sequel in the future but cashed in all your goodwill on a run of mediocre entries

(see Infinite Warfare for an example of that).

When you’re

cranking out sequels simply to keep to a schedule, you’re only going to damage

the long-term credibility of the series in question. Now when I think about

Mass Effect, instead of my brain saying, 'Yeah, that was a great series,' now it

also adds, 'Shame about Andromeda.' As for Assassin’s Creed, its ludicrous

number of sequels is the first thing I think about; it’s what the series has

become known for. This might not

matter to company executives in the short term, but when the money dries up and

a legacy is all a game has left, it matters a whole lot more. It also matters

if you do have a good idea for a

sequel in the future but cashed in all your goodwill on a run of mediocre entries

(see Infinite Warfare for an example of that).

This leads

on to a more serious point, which is that when a publisher keeps demanding

sequels beyond the point where a developer has reasons for making them, they’re

actively stifling the creativity of that studio, the possibility that it might create the next Assassin’s

Creed rather than merely another Assassin’s

Creed. Imagine what BioWare Edmonton might have done had it had the chance

to stamp its identity on its own creation rather than being lumbered with

a huge IP with no good reason to come out of retirement and the impossible expectations

of delivering on that. Imagine if Raven Software could create a game again

rather than spending eternity designing map packs for Call of Duty.

If all big publishers do is regurgitate old ideas,

keeping them on life support long after they should have died, then there is no

room for new ideas to grow. There’s some onus on us as consumers too. We need

to become more accepting that everything has a natural end point and be

more open to developers trying new things rather than demanding more of the

same. This is why, much as I’d love to play more Witcher, I’m happy CDProjekt

has decided to end on the stratospheric high it has. Nothing can be new and

fresh and exciting forever, and eventually the best it can do is make way for

the next new idea.

If all big publishers do is regurgitate old ideas,

keeping them on life support long after they should have died, then there is no

room for new ideas to grow. There’s some onus on us as consumers too. We need

to become more accepting that everything has a natural end point and be

more open to developers trying new things rather than demanding more of the

same. This is why, much as I’d love to play more Witcher, I’m happy CDProjekt

has decided to end on the stratospheric high it has. Nothing can be new and

fresh and exciting forever, and eventually the best it can do is make way for

the next new idea.

MSI MPG Velox 100R Chassis Review

October 14 2021 | 15:04

Want to comment? Please log in.