I often think that, had Bulletstorm been a commercial success, the last decade of first-person-shooters would have shaken out very differently. People Can Fly’s wilfully dumb, secretly ingenious, altogether fantastic FPS infamously sold a measly number of copies when it first launched in 2011. The game’s reputation has grown somewhat in the interceding years, but I still don’t think its anywhere near as lauded as it deserves to be.

There are layers to this, but it all forms around the fact that Bulletstorm understands shooters are generally better when they focus on the how, rather than the why. When FPS’ get too focussed on why you need to turn hundreds of people quivering mince, they start to struggle, because such calamitous slaughter is generally frowned upon. This is partly why nearly every Call of Duty since 4 has been mediocre at best, because they’re too busy trying to justify all their patently unjustifiable actions with increased levels of realism and outlandish, implausible storytelling.

Bulletstorm, by comparison, doesn’t care one whit about the why. Instead, it focuses almost entirely on how you’re going to kill someone, how you’re going to snuff out that screaming radioactive mutant’s soul in the most stylish, the most spectacular, or the most gruesome way possible. Where so many other shooters try to frame themselves in the right, Bulletstorm justifies its existence by being so gleefully wrong.

At the heart of this is, of course, the skillshots system, which like Shadow of Mordor’s Nemesis system and Portal’s portals, is one of the mechanics that deserves to be in so many more games than it is. For the unfamiliar, think Tony Hawk’s Pro Skater, but with guns instead of skateboards, and you’re well along the road to understanding it. You can kill enemies the boring, normal way, crouching behind cover and popping up to pop heads, but pulling off trick-shots scores you points. These are spent on buying ammo and upgrading your weapons, in turn enabling you to perform more trick-shots.

There are well over a hundred of these skill-shots to discover, ranging from the grisly to the cartoonishly depraved. Kicking an enemy before shooting them, for example, earns you the “Bullet-Kick” bonus. Kicking an enemy into a giant cactus, meanwhile earns you the bonus “Pricked.” But the skillshots systems truly comes into its own when combined with Bulletstorm’s wonderfully eclectic array of weapons. The assault rifle’s alt-fire unleashes a single, hyper-powered piercing shot which, if you can hit two or more enemies with it, earns you the bonus “X-Ray.” You can combine this with another skillshot for headshotting enemies with the alt-fire.

More eclectic skillshots can be obtained with the weapons like flail gun, which wraps enemies in exploding boluses and turns them into living bombs. Even the humble sniper rifle has steerable bullets, alongside charge shot that makes them remotely explodable, offering dozens of different ways to dispatch your opponents in style. But my favourite weapon, unlocked near the end of the game, fires enormous drill-bits that not only impale enemies on walls, but cause them to spin violently around, their limbs being gradually torn off by the centrifugal force. It’s utterly ridiculous, and an absolute joy to wield.

The skillshots system is one of the smartest and most entertaining FPS mechanics ever devised, and alone makes Bulletstorm worth playing. But there’s more Bulletstorm deserves credit for too. The story and setting are more original and interesting than the vast majority of other shooters. This is generally less remarked upon, likely due to the game’s often puerile, fratboy-ish tone. And yes, there are lots of jokes about genitals and venereal disease. But beneath this is a blisteringly paced sci-fi tale about revenge and redemption in one of the strangest locations of any FPS.

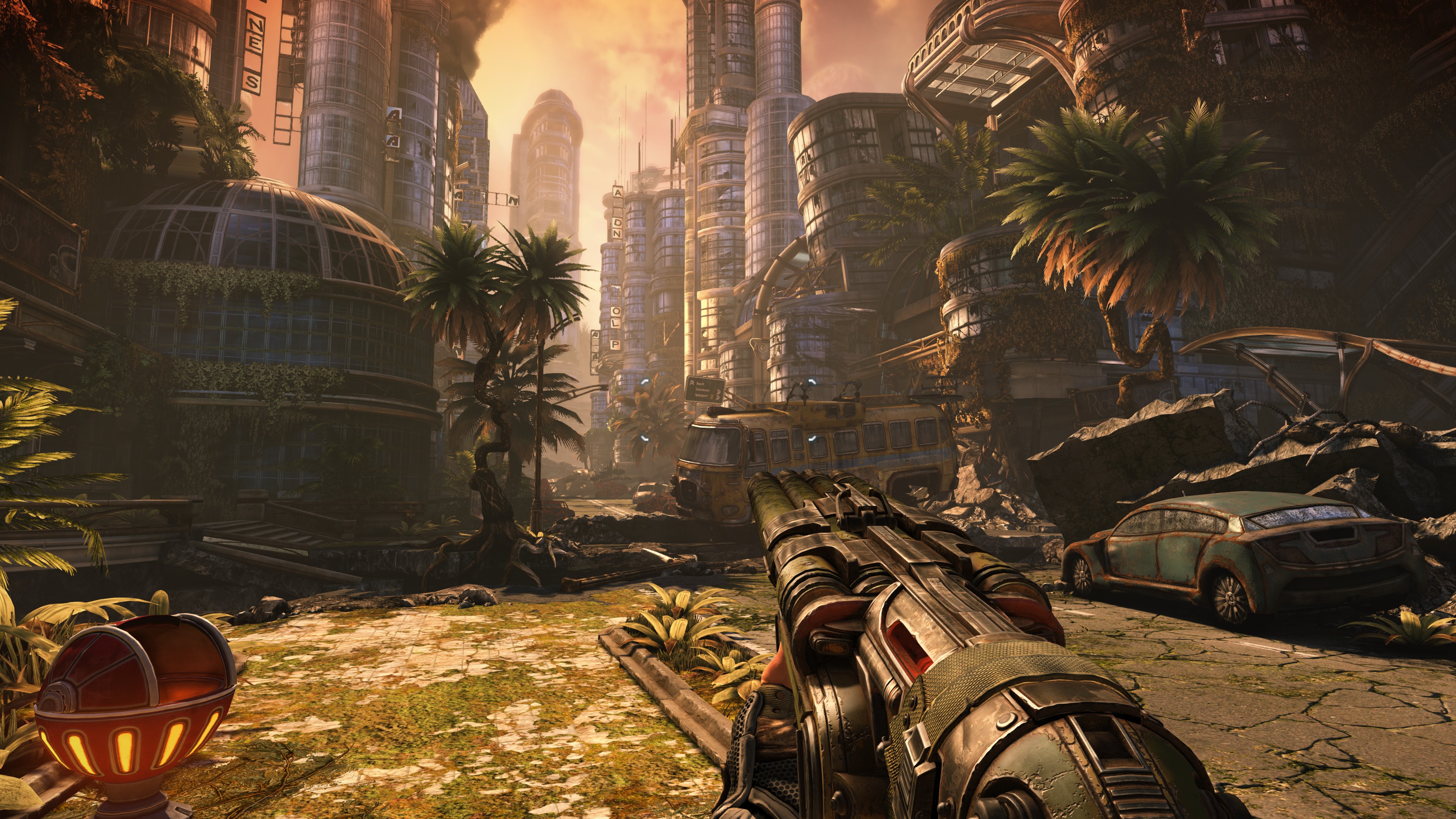

Bulletstorm begins where most other games end, as Grayson Hunt and his team of mercenary scumbags attempt a drunken assault on the flagship of General Sarrano, who Hunt used to work for until he discovered his team was being used to assassinate innocent people. Hunt’s wild attack quickly morphs into a suicide charge that kills most of his crew and cripples both Sarrano’s ship and his own. The two vessels crash onto a hostile alien planet once intended as a luxurious holiday resort, before the radiation, deadly lightning storms, and giant alien monsters put paid to that idea. Emerging from the wreckage, Grayson and his critically-wounded comrade Ishi seek a way off planet, as Hunt attempts to balance his desire for revenge with his need to save the life of his last remaining friend.

Bulletstorm never pretends that its protagonist is anything other than a terrible person. Indeed, the game is largely about Grayson coming to terms with all the horrible things he’s done, the friends he has failed and the innocents he has murdered. Stranded in an alien hell that he thoroughly deserves to be in, Bulletstorm is about Grayson trying to scrape together what little humanity he has left in a place that long ago lost its own. Bulletstorm generally plays its setting for laughs, but along the way are little nods to the humanitarian disaster that has unfolded on the planet, from the giant, underground prison where the convicts used to build the resort were held, to the mountains of suitcases left abandoned at the planet’s spaceport. For all its toilet humour, Bulletstorm spins a surprisingly coherent sci-fi tale.

Bulletstorm is also one of the most spectacular shooters around, blasting through a relentless assault of stunning set-pieces. Within the first two hours, you’ve survived a spaceship-crash, been chased on a train by a giant grindwheel, escaped the maw of Godzilla’s extra-terrestrial cousin, and mowed down enemies with your own remote-controlled robot dinosaur. Yet for all its scripted fireworks, the game never loses sight of the dynamic core that makes it so distinctive, and so much fun.

As you can probably guess, I think Bulletstorm is a superb shooter, and one which has aged extremely well. Not perfectly, however. For one, it’s a much browner game than I remember. Aesthetically it’s a strange game, in some places it’s extremely colourful, but most of the game is smeared with a sepia filter that sucks a lot of the vibrancy out of environments.

Bulletstorm also suffers from certain “modern” conventions of its time. For a game about pulling off cool weapon-based tricks, its player movement and general level design are surprisingly limited. The game would benefit hugely from more arena-styled levels in the vein of Doom Eternal, offering multiple angles of attack and generally giving the player more freedom to move and experiment with their weapons. Indeed, perhaps its greatest flaw is the prescribed nature of its Skillshots. As well as levels being spatially restrictive, the skillshot system only recognises specific tricks, having no space to understand more creative combinations of your own.

It’s an oversight that probably would have been rectified in a sequel, had Bulletstorm ever received one. But it didn’t, and the legacy of the game more or less ended at launch. One could possibly argue, that there are glimmers of Bulletstorm in id’s recent Doom games, which also encouraged players to consider the how of their killing, albeit for the purpose of staying alive rather than bragging rights. But you’d be hard-pushed to trace a clear link between the two. For the most part, Bulletstorm stands alone as a brash, bizarre, and brilliant anomaly in the FPS canon.

MSI MPG Velox 100R Chassis Review

October 14 2021 | 15:04

Want to comment? Please log in.