Given you’re often floating through cramped corridors littered with floating objects, this provides a fairly challenging obstacle. Sadly, the sense of your suit being damaged is not particularly well communicated, meaning the sense of peril is underwhelming, and it’s difficult to ascertain precisely how degraded the suit is. Active hazards are also surprisingly scarce. Occasionally you’ll have to dodge a dangling electrical wire, or weave between the spinning sails of a solar array, but such obstacles are an occasional distraction as opposed to the meat of the game.

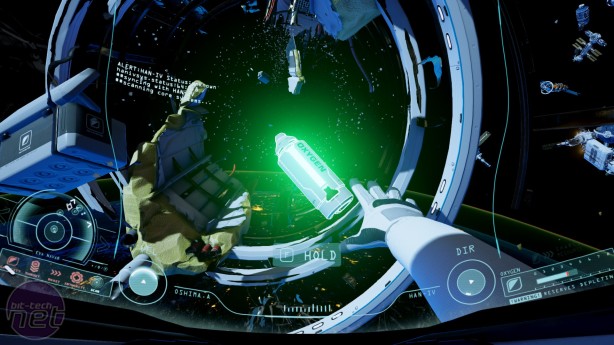

Indeed, ADR1FT’s most damaging flaw is its dire shortage of distractions. Interactively the game verges on barren. Aside from picking up Oxygen canisters, entering suit-repair stations, and interacting with computer terminals, there’s very little for the player to actually do in ADR1FT. Worse, all of these actions are filtered through the same context sensitive control system, stripping them of their uniqueness like a farmer clearing a stretch of virgin woodland to graze sheep on. Ultimately, you aren’t really interacting with the environment, instead you’re pressing a button and watching your avatar interact with the world for you.

This wouldn’t be such a problem if the environments were interesting to explore, but after the initial wow-factor, ADR1FT quickly descends into numbing routine. Oshima’s main objective in the game is to switch on the Han IV’s four computer mainframes, in order to activate the escape shuttle and fly safely back to Earth. Each of these mainframes is located in a separate part of the station, yet each one requires exactly the same process to activate – navigate the station, avoid a few hazards, press a button. At no point in this process does anything surprising or unexpected happen, the station’s integrity doesn’t deteriorate or improve beyond the initial disaster. Given ADR1FT is about arguably the most desperate survival situation imaginable, its plot-beats are astonishingly dull.

This is not to say that ADR1FT has nothing to offer from a narrative perspective. Both the writing and acting are actually rather good. The unfolding story of who is responsible for the disaster and why is particularly intriguing. Elsewhere though, the storytelling priorities are misguided, focussing almost exclusively on the plights of dead men and women rather than keeping us in the moment. Stupidly, Oshima cannot communicate at all with Earth, meaning we must sit for large amounts of time in frustrated silence, listening to one-way messages from Ground Control as they try to get through.

Other than that, the only company Oshima has are the audio-logs of her deceased crewmates. Again, these logs are well acted and impressively characterised, although I struggled to reconcile some of the character’s traits with the logic of the game’s world. One crewmember, for example, is a recovering drug addict who used to steal hospital supplies to fuel his addiction, while another is dying of cancer. I find it difficult to believe that any high-risk spacefaring mission, which ADR1FT openly states as part of its near-future fiction, would let a dying man or a drug addict take part in such a dangerous endeavour when there are so many other potential candidates available.

Despite Three One Zero’s commendable work on creating a convincing environment in 3D space, ADR1FT ultimately proves something of a misfire. I’ve played several similar, narrative-led first person games recently, such as the excellent Firewatch, and the brilliant SOMA late last year, and I was seriously looking forward to ADR1FT as the next step forward in first-person exploration games. After the first few minutes, however, I struggled to muster much enthusiasm for any of its components, and by its conclusion the game left me cold.

Indeed, ADR1FT’s most damaging flaw is its dire shortage of distractions. Interactively the game verges on barren. Aside from picking up Oxygen canisters, entering suit-repair stations, and interacting with computer terminals, there’s very little for the player to actually do in ADR1FT. Worse, all of these actions are filtered through the same context sensitive control system, stripping them of their uniqueness like a farmer clearing a stretch of virgin woodland to graze sheep on. Ultimately, you aren’t really interacting with the environment, instead you’re pressing a button and watching your avatar interact with the world for you.

This wouldn’t be such a problem if the environments were interesting to explore, but after the initial wow-factor, ADR1FT quickly descends into numbing routine. Oshima’s main objective in the game is to switch on the Han IV’s four computer mainframes, in order to activate the escape shuttle and fly safely back to Earth. Each of these mainframes is located in a separate part of the station, yet each one requires exactly the same process to activate – navigate the station, avoid a few hazards, press a button. At no point in this process does anything surprising or unexpected happen, the station’s integrity doesn’t deteriorate or improve beyond the initial disaster. Given ADR1FT is about arguably the most desperate survival situation imaginable, its plot-beats are astonishingly dull.

This is not to say that ADR1FT has nothing to offer from a narrative perspective. Both the writing and acting are actually rather good. The unfolding story of who is responsible for the disaster and why is particularly intriguing. Elsewhere though, the storytelling priorities are misguided, focussing almost exclusively on the plights of dead men and women rather than keeping us in the moment. Stupidly, Oshima cannot communicate at all with Earth, meaning we must sit for large amounts of time in frustrated silence, listening to one-way messages from Ground Control as they try to get through.

Other than that, the only company Oshima has are the audio-logs of her deceased crewmates. Again, these logs are well acted and impressively characterised, although I struggled to reconcile some of the character’s traits with the logic of the game’s world. One crewmember, for example, is a recovering drug addict who used to steal hospital supplies to fuel his addiction, while another is dying of cancer. I find it difficult to believe that any high-risk spacefaring mission, which ADR1FT openly states as part of its near-future fiction, would let a dying man or a drug addict take part in such a dangerous endeavour when there are so many other potential candidates available.

Despite Three One Zero’s commendable work on creating a convincing environment in 3D space, ADR1FT ultimately proves something of a misfire. I’ve played several similar, narrative-led first person games recently, such as the excellent Firewatch, and the brilliant SOMA late last year, and I was seriously looking forward to ADR1FT as the next step forward in first-person exploration games. After the first few minutes, however, I struggled to muster much enthusiasm for any of its components, and by its conclusion the game left me cold.

MSI MPG Velox 100R Chassis Review

October 14 2021 | 15:04

![Event[0] Review](http://images.bit-tech.net/content_images/2016/09/event0-review/featured_double.jpg)

Want to comment? Please log in.