TNMOC, CCS open EDSAC rebuild exhibit

November 27, 2014 | 11:08

Companies: #bletchley-park #ccs #history #tnmoc

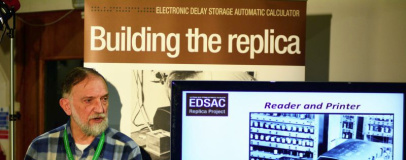

The National Museum of Computing (TNMOC) at Bletchley Park has officially opened its EDSAC display at an event last night presided over by Acorn co-founder Hermann Hauser.

A rebuild of the long-lost original, the Computer Conservation Society's (CCS') EDSAC Project was announced back in 2011 as an attempt to recreate Maurice Wilkes' Electronic Delay Storage Automatic Calculator (EDSAC) system, and is generally considered - by British computer historians, at least - to have been the world's first practical general-purpose digital computer, with the US ENIAC having been specialised for the computation of artillery tables for the military. EDSAC has a particularly special place in the history books, having inspired the creation of a variant that would be known as the Lyons Electronic Office (LEO) - unarguably the world's first computer to be owned and operated by a privately-owned business for the purposes of day-to-day operations.

The project has hit some major milestones since its inception, including the production of replica chassis parts in 2013 and the discovery of unique circuit diagrams thought long lost in June this year. Now, the project - which is due to complete late next year - is available for public viewing following the official opening of the exhibit last night.

At the event, opened by Acorn co-founder and home computing pioneer Hermann Hauser, project member Bill Purvis demonstrated the inputting of a program and the output of results on a system which predates the use of keyboards and cathode ray tubes as computer input and output devices, while Chris Burton gave life to the machine with the landmark activation of EDSAC's internal clock.

'Reconstructing EDSAC is proving to be a fascinating challenge with lots of surprises. We are incredibly fortunate to be able to call of a volunteer team with an extraordinarily rare skill set. The team includes students of the original computer pioneers and members of the last generation to be trained in the use of thermionic valves, the key component of EDSAC - which has 3,000 of them,' explained Andrew Herbert, leader of the EDSAC Project. 'But even with those rare skills, the task is not straightforward. Our skilled team has to forget knowledge that it painstakingly acquired in the development of later landmark machines like the 1950’s Ferranti Pegasus and the 1960’s Elliott computers. We don’t have blueprints to follow, so to create an authentic EDSAC we have to adopt a 1940’s mindset to re-engineer, redesign the machine. We face the same challenges as those remarkable pioneers who succeeded in building a machine that transformed computing.'

'This is truly a remarkable project that brings history to life for its participants and for the viewing public,' added Computer Conservation Society co-founder Doron Swade. 'EDSAC provided, for the first time, reliable computing capability for scientists. It could be said that EDSAC invented the user as a distinct class of practitioner. To have a working reconstruction of the computer that trail-blazed both programming practices and computational services for scientific research cannot fail to interest casual observers and more importantly inspire young people with their careers ahead of them. It shows that computer conservation is flourishing and contributing real value in the modern world.'

More details of the EDSAC Project and the machine itself are available on the official website.

A rebuild of the long-lost original, the Computer Conservation Society's (CCS') EDSAC Project was announced back in 2011 as an attempt to recreate Maurice Wilkes' Electronic Delay Storage Automatic Calculator (EDSAC) system, and is generally considered - by British computer historians, at least - to have been the world's first practical general-purpose digital computer, with the US ENIAC having been specialised for the computation of artillery tables for the military. EDSAC has a particularly special place in the history books, having inspired the creation of a variant that would be known as the Lyons Electronic Office (LEO) - unarguably the world's first computer to be owned and operated by a privately-owned business for the purposes of day-to-day operations.

The project has hit some major milestones since its inception, including the production of replica chassis parts in 2013 and the discovery of unique circuit diagrams thought long lost in June this year. Now, the project - which is due to complete late next year - is available for public viewing following the official opening of the exhibit last night.

At the event, opened by Acorn co-founder and home computing pioneer Hermann Hauser, project member Bill Purvis demonstrated the inputting of a program and the output of results on a system which predates the use of keyboards and cathode ray tubes as computer input and output devices, while Chris Burton gave life to the machine with the landmark activation of EDSAC's internal clock.

'Reconstructing EDSAC is proving to be a fascinating challenge with lots of surprises. We are incredibly fortunate to be able to call of a volunteer team with an extraordinarily rare skill set. The team includes students of the original computer pioneers and members of the last generation to be trained in the use of thermionic valves, the key component of EDSAC - which has 3,000 of them,' explained Andrew Herbert, leader of the EDSAC Project. 'But even with those rare skills, the task is not straightforward. Our skilled team has to forget knowledge that it painstakingly acquired in the development of later landmark machines like the 1950’s Ferranti Pegasus and the 1960’s Elliott computers. We don’t have blueprints to follow, so to create an authentic EDSAC we have to adopt a 1940’s mindset to re-engineer, redesign the machine. We face the same challenges as those remarkable pioneers who succeeded in building a machine that transformed computing.'

'This is truly a remarkable project that brings history to life for its participants and for the viewing public,' added Computer Conservation Society co-founder Doron Swade. 'EDSAC provided, for the first time, reliable computing capability for scientists. It could be said that EDSAC invented the user as a distinct class of practitioner. To have a working reconstruction of the computer that trail-blazed both programming practices and computational services for scientific research cannot fail to interest casual observers and more importantly inspire young people with their careers ahead of them. It shows that computer conservation is flourishing and contributing real value in the modern world.'

More details of the EDSAC Project and the machine itself are available on the official website.

MSI MPG Velox 100R Chassis Review

October 14 2021 | 15:04

Want to comment? Please log in.