Price: £39.99

Developer: Bend Studio

Publisher: Playstation Mobile, Inc

Platform: PC

Days Gone is the Platonic ideal of an open world game, featuring precisely you would expect from the genre and basically nothing else. It has a big pretty environment. Its story is about a morally ambivalent gruff white man. It has main and side quests that result in cash rewards. It has melee and ranged combat. It has a cover system. It has a stealth system. It has an upgrade system. It sort of has a faction system. It has a crafting system that isn’t really a crafting system. Its primary enemies are zombies, the platonic ideal of a video-game adversary.

It is the industry standard for AAA videogames, the bread and butter, the Ur experience, the mould from which all other big-budget games are cast. It isn’t a terrible game, neither is it a great game. It is an entirely median title, intermittently dragging itself up to the status of “decent”, and slightly more frequently stumbling in the conveniently placed manure-pile of “dodgy.”

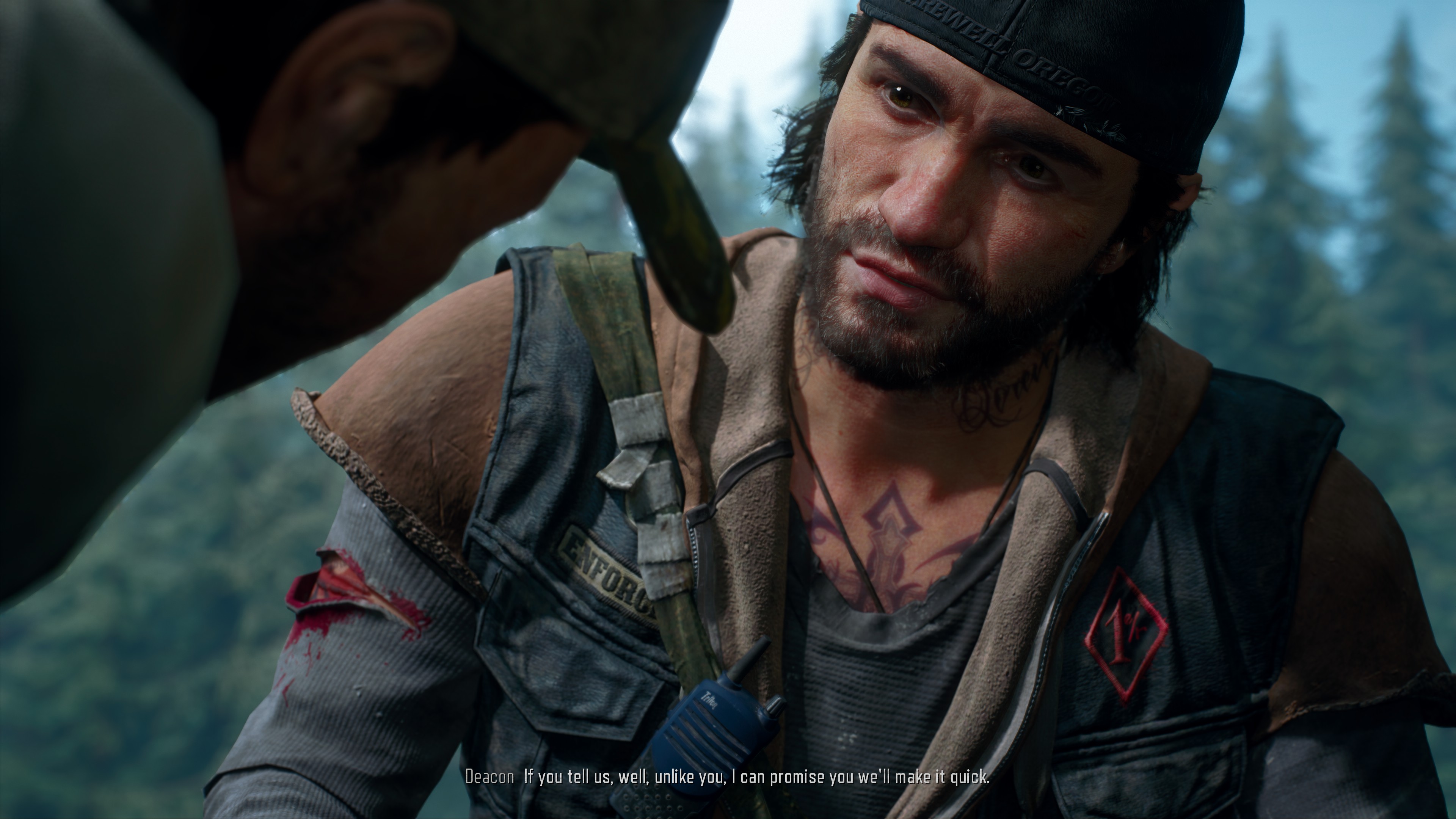

Days Gone tells the story of Deacon St John. Deacon loves three things, his wife, his bike, and his friend William Gray, also known as “Boozer” or “Boozeman”. He isn’t known as Boozy McBoozeface, which is a shame because it would at least be funny as well as stupid.

In the game’s introductory hour, we learn Deacon is sad because the three pillars of his life are in trouble. His wife is missing and presumed dead. His bike has been stolen and sold for parts by a local settlement. Boozehound is seriously injured after being attacked by a group of crazed bandits. Oh, and there’s a zombie apocalypse happening, although Days Gone refers to them as “Freakers”, once again demonstrating its questionable talent for naming things.

Deacon plans to ride north to start a new life, but he’s held back by the memory of his wife, the injury to his friend, and the cannibalising of his bike. To solve these problems, he must work with various settlements dotted around the game’s slice of Oregon, rescuing survivors and gathering supplies while also battling freakers and marauding gangs.

In other words, standard zombie apocalypse stuff. In both environment design and broad plot Days Gone does little to differentiate itself from the undead pack. The world is largely indistinguishable from that seen in the Walking Dead. Between chunks of picturesque forest loomed over by snowcapped mountains, you’ll explore abandoned American towns, shanty-like survivor settlements, dilapidated medical and military facilities, and so on.

The most original idea Days Gone has is to put you on a bike. Formerly a member of a biker gang, Deacon travels the world on the kind of grunting, chrome-plated American chopper you can hear coming from the neighbouring universe. Given how noise attracts the Freakers that prowl Days Gone’s world, this mode of transport makes about as much sense, as, well, having a friend called Boozeking. That said, it is an enjoyable way to traverse the world, fast enough to keep your fingers away from the fast-travel key, and also nimble enough to navigate the post apocalypse’s many piles of detritus and abandoned cars.

The bike also acts as a thoroughfare into the game’s light survival systems, as it regularly requires refuelling and repairing. This can be done in exchange for cash at settlements, but you can also do the job yourself by salvaging scrap from other vehicles and scouring the world for fuel tanks. And since you’re in town anyway, it’s usually worth looking around for crafting materials to make Molotov cocktails, medical supplies, and resources to craft more effective melee weapons like a spiked baseball bat.

The exploration element is probably the bit of Days Gone I like the most, although it’s a shame the world isn’t more storied. Unlike, say, Red Dead Redemption 2, which ensures every location has something interesting about it that makes it worth visiting, Days Gone’s world is largely devoid of the history of the people who once lived there.

Quiet and contemplative moments in Days Gone are relatively rare, however. Whether on a mission or just exploring of your own free will, combat is never far away. When blood starts to fly, it’ll mainly be that of humans or zombies. Personally, I preferred fighting humans. Guns in Days Gone feel lethal, and in the early stages at least, ammo is a scarce resource. Shots have real impact, while groups of human enemies behave convincingly, crying out in anger and anguish when their comrades are gunned down.

Zombie combat, by comparison, is mainly about running away from enemies while occasionally turning to pop off a few rounds. It isn’t terrible, but clearing areas of Freakers can be somewhat tedious, at least until the game introduces bigger weapons and more numerous Freaker types.

While Freakers are usually dispersed over a wide area, occasionally you’ll encounter them in hordes. These vast, seething masses of undead bodies will chase you relentlessly and kill you in seconds if they catch you. From a technical perspective, the hordes are a remarkable achievement, but in practice it’s a long time before they’re much fun to fight. Your weapons and equipment won’t be fit for taking on hordes until at least 15 or 20 hours into the game.

The hordes are also emblematic of Days Gone’s main mechanical problem, which is a failure to make the most of its dynamic potential. At one point while travelling, I was attacked by some marauders on a road, which attracted the attention of a nearby horde. After dealing with the marauders, the horde came for me. I was nowhere near equipped to deal with it, but I spotted a nearby bandit camp and ran into it. The bandits began shooting at the horde, distracting the Freakers long enough for me to get away.

This little escapade highlights the potential for dynamic zombie fun, for playing enemies off one another. Sadly, such opportunities are rare. Instead of being allowed to roam freely, both hordes and bandits are mainly squirrelled in specific locations, acting as “Activities” for the player to complete. This compounds Days Gone’s sense of being a largely static world.

This would be less of a problem if the story was gripping, but instead it’s derivative and extremely long-winded. There are a few touching moments, alongside a handful of interesting characters such as Tucker, whose grandmotherly appearance belies her role as the unapologetic head of a slave camp.

Unfortunately, Deacon is not one of those characters. Neither charismatic nor particularly likeable, Deacon is supposed to come across as sensitive but still ruggedly masculine. Yet his reactions are often those of a petulant child. He needlessly escalates difficult conversations, reacts to problems like a disgruntled teenager, and generally acts like a dick to people who are trying to help him. He also has this weird propensity for muttering under his breath in a way that sounds completely unconvincing, and will occasionally yell loudly at bike’s radio, which given there are zombies everywhere makes him look like a complete idiot.

In the end, Days Gone is just another zombie survival game. It may be bigger and prettier than the others, but it brings little that’s either original or exceptional to both open world gaming and zombie survival fiction. There is fun to be had biking around its picturesque woodland landscapes, but there are better zombie games and better open worlds.

MSI MPG Velox 100R Chassis Review

October 14 2021 | 15:04

Want to comment? Please log in.