Digital Economy Act Judicial Review Analysis

April 22, 2011 | 09:34

Companies: #government #open-rights-group

Is an IP Address Enough Evidence?

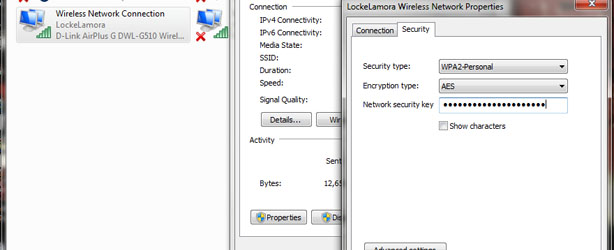

While the policy review ultimately concerned technicalities with European law, the key questions about the bill for consumers concern the implications of the act itself. Why do so many people consider it to be ill-judged?There are several components of the DEA that are causing controversy. One of these is the letter-writing policy. Bradwell (of the Open Rights Group) explains that this is where 'apparently-infringing IP addresses are connected to ISPs, who then have to identify the subscriber that corresponds to it, and then a letter gets sent to the subscriber.' After three letters, action is supposed to be taken against the subscriber, such as bandwidth throttling.

This presents a major problem, though; is an IP address really sufficient evidence to limit someone's access to the Internet? After all, it's easy enough for an uninformed broadband subscriber to have their unsecured WiFi network hijacked, and one IP address can also hide several people in a shared house.

The BPI argues that broadband account holders need to be better educated about copyright and the

new legislation, so that their IP address isn't associated with copyright infringement

'One of the things that we submitted to the court was that IP address evidence gathered in the way that's suggested just isn't sufficient,' says Bradwell. 'We're concerned that potentially innocent people will be targeted by this, and that there will be an insufficient appeal process. Ultimately, if these technical measures are taken forward at whatever point in the future, then people who've not been proved to be guilty of doing anything wrong will have their bandwidth throttled, or be suspended and so on.'

Is this policy really ill-judged, though? We discussed the issues behind using IP addresses as evidence of copyright infringement with Adam Liversage, director of communications at the British Phonographic Industry (BPI), and while he emphasised that the BPI hoped that no innocent people would be affected by the bill, he also said that it's important that broadband subscribers are educated about the legislation and copyright.

Content providers such as the BPI see it as the broadband subscriber's responsibility to ensure that their IP address isn't associated with copyright infringement; if they're all well educated about the issues, then they suggest that there isn't really a problem with the legislation.

Another key issue of the DEA is the effective blocking of sites that are deemed to be illegal. 'It's hard to know what the list will look like,' says Bradwell, 'but it will be things like Pirate Bay and torrent sites like that, and I think potentially some cyberlockers.'

So who gets to decide which sites are blocked? 'That's a really good question,' says Bradwell. 'One of the key questions here is who decides what's acceptable for people to see or not see, and on what basis, and it will be really difficult to prove that a service is exclusively used for the purpose of infringing copyright and to give those that are targeted sufficient leeway to establish any wrongdoing before any action is taken. We're really concerned that the way this seems to be moving forward is the discussion of some kind of self-regulatory model.'

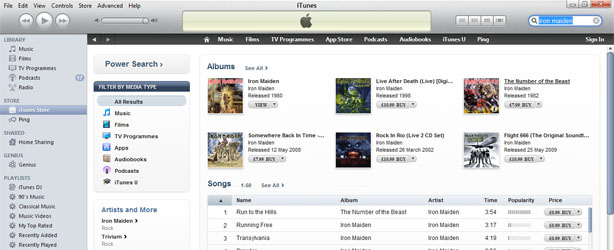

Is it reasonable to be effectively censoring parts of the Internet? 'In essence, there are websites out there that are wholly engaged with offering illegal copyrighted material,' says Liversage, 'either free or pay sites, and it's our opinion that those are the sites that are doing a lot of damage to the creative industries in the UK. We think it's reasonable to consider ways in which those websites can be blocked.'

The content industries argue that there's no danger of accidentally downloading viruses or trojans from legitimate download sites

The content industries argue that there's no danger of accidentally downloading viruses or trojans from legitimate download sitesLiversage also points out that sites such as this are 'not only doing damage to the creative industries and the people who work in them; they're also misleading consumers, and this is an area of concern to us. If you go to search engines and type in things like "repertoire," "download" and "MP3," you're pointed to a range of sites which look convincingly legal, but which are in fact not. If you're dealing with illegal sites, you have no guarantee about the quality of product that you're getting, and you can find yourself at risk of all sorts of other issues, like viruses and Trojans, which simply don't occur on the legal sites that are licensed in the UK.'

Even so, the Open Rights Group insists that the measures in the DEA will not provide a fair and effective solution to online copyright infringement. There's no easy answer to solving the problem of online copyright infringement, particularly if you want to appease both consumers and rights holders. While there's no easy solution, though, Bradwell suggests that a satisfactory answer will only be reached if the government properly consults people who understand the Internet and the nature of the problem.

MSI MPG Velox 100R Chassis Review

October 14 2021 | 15:04

Want to comment? Please log in.