Price: £14.99

Developer: Matt Makes Games

Publisher: Matt Makes Games

Platforms: PC, PS4

Version Reviewed: PC

I find myself in two minds about Celeste, the new precision platformer from the creators of Towerfall Ascension. It has a noble goal, aiming to be a kind of Super Meat Boy for people who don't like Super Meat Boy, namely a deliberately challenging game that aims to reward and encourage improvement rather than sneering derisively at the less skilful. It's a neat idea and one that I applaud.

On the other hand, and I'm not going to lie, I am so very tired of 'It's a pixel platformer, but X!' games, which overlay the same rudimentary mechanics with an allegory for depression or something. This isn't to say games shouldn't explore such topics – they absolutely should. I'd merely like to see it done in genres that aren't bloody jumping games – Hellblade being the best recent example. While I admire certain aspects of Celeste, I don't think it does enough to escape this criticism. Moreover, in some ways I found it to be actively annoying to play, and not because at times it becomes keyboard-splittingly difficult.

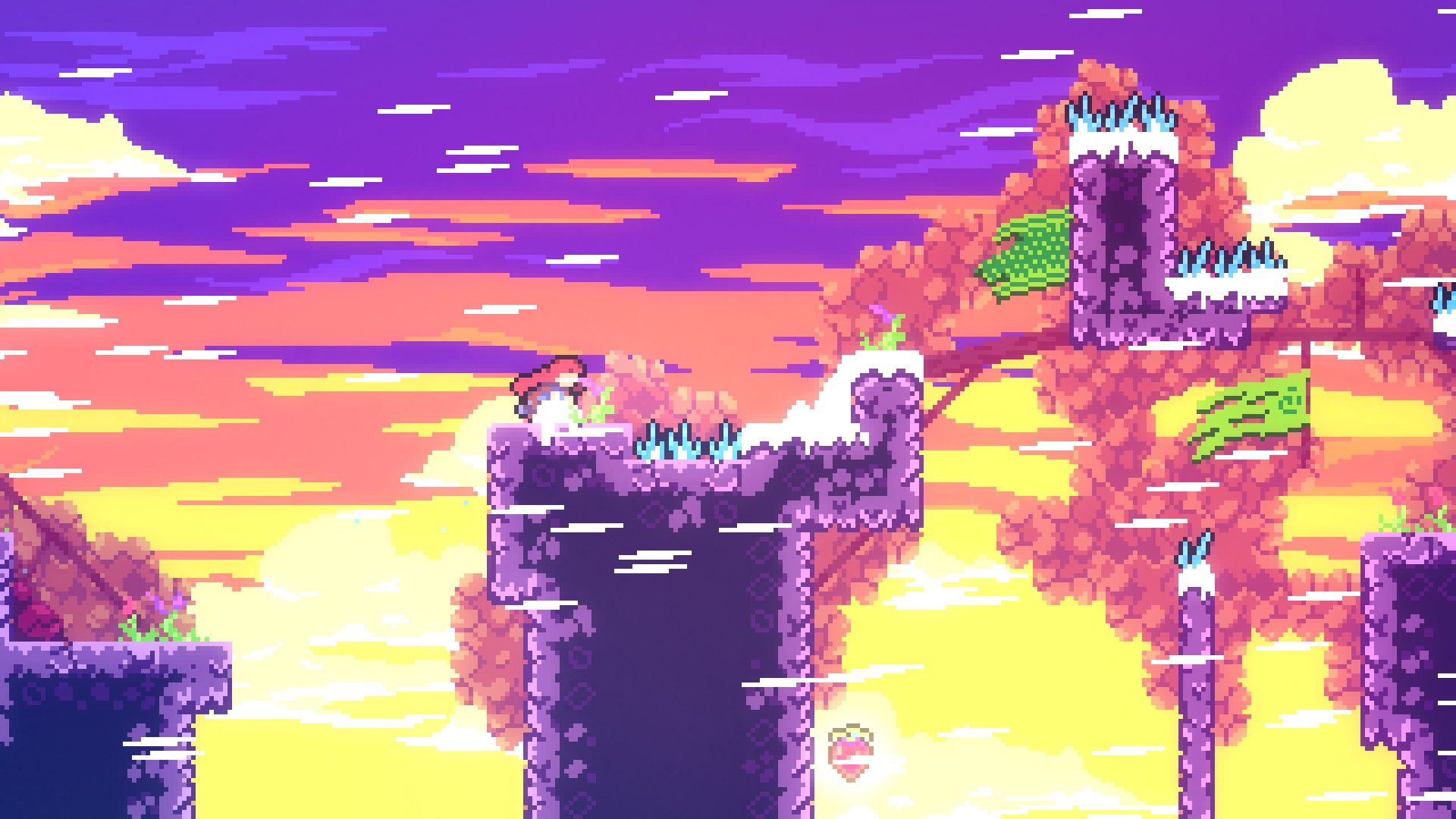

Celeste's story centres on a young woman called Madeline, a kind and generous personality buried inside a stubborn and somewhat recalcitrant shell. Madeline has set it upon herself to climb Celeste Mountain, a jagged, snowy peak that is a notoriously difficult ascent, and is the site of multiple aborted attempts at human settlement. The few people who still reside upon its slopes are various shades of eccentric bordering on mad.

Generally, the tale can be read as a metaphor for overcoming personal challenges, but more specifically it's an allegory for overcoming anxiety. Alongside the mountain itself, Madeline's self-doubt is externalised in many of the characters she encounters. These range from an old woman who repeatedly asks Madeline if she's ready give up and to turn back, to the manager of a crumbling, vacant hotel whose inability to escape his own downward spiral is a reflection of the worst-case scenario of Madeline's own interior conflict.

It is, for the most part, a well-told tale, although there are bits of it I don't like, which I'll get onto later. In any case, the idea intertwines well with Celeste's own take on precision platforming. At a core level, Celeste bears a lot in common with games like Super Meat Boy and VVVVVV. The central mechanics are stripped right back to movement, jumping, the ability to climb, and a satisfying “dash” manoeuvre which allows Madeline to propel herself in any direction.

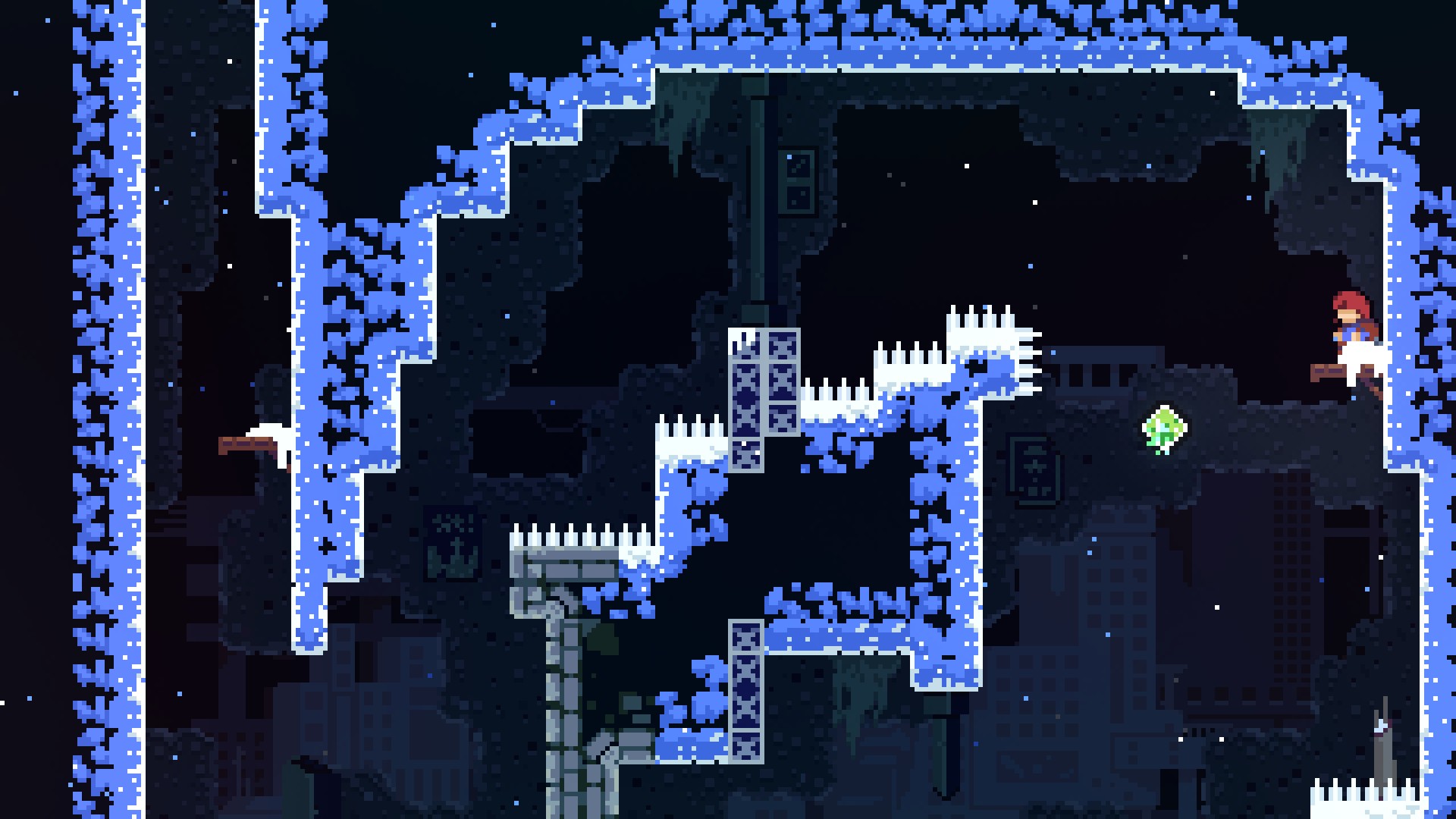

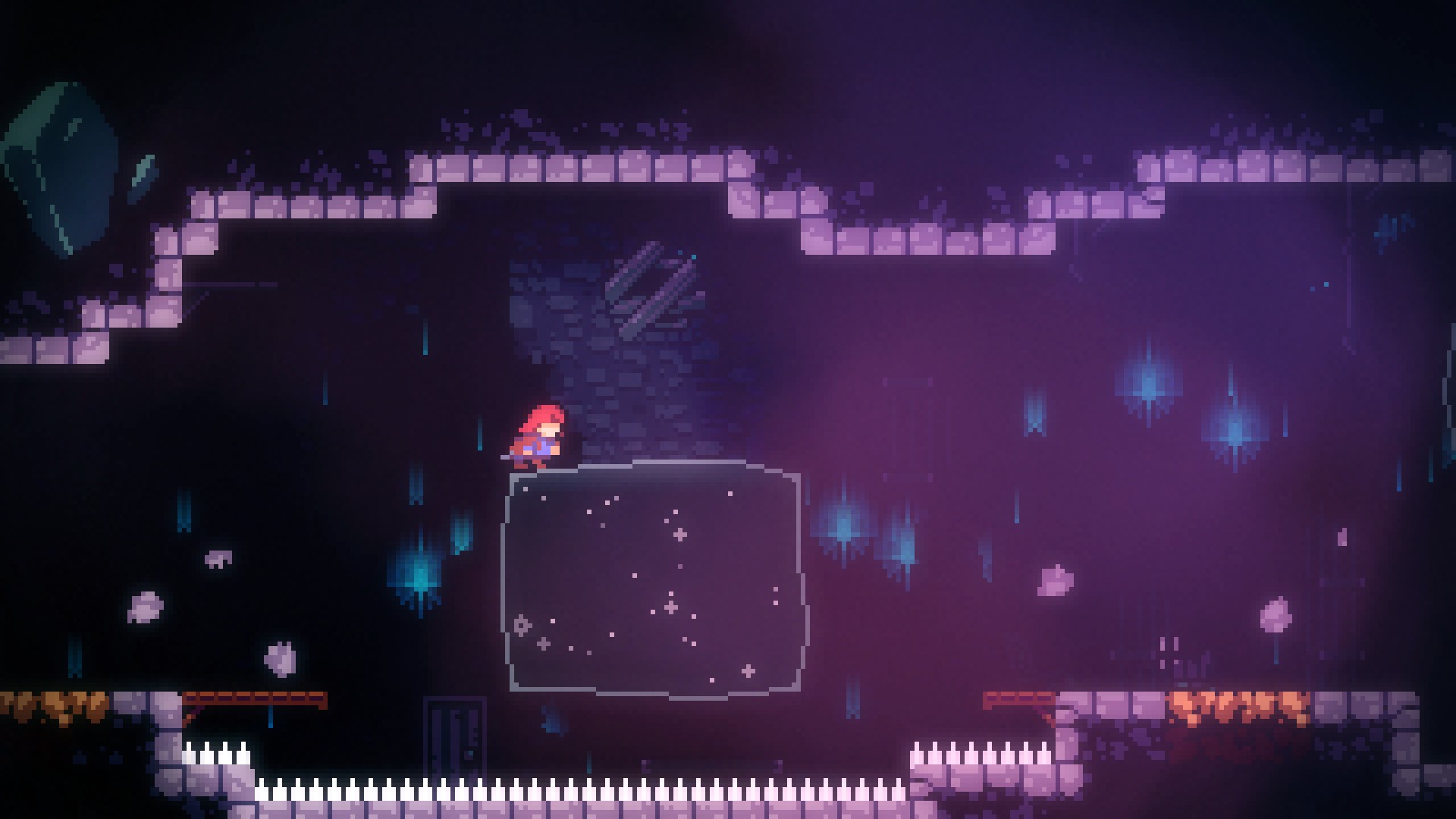

The game's complexity, meanwhile, emerges from the level design. Each of the game's eight chapters introduces a new sub-mechanic, from bouncy clouds that allow Madeline to jump higher, to glittering, gelatinous blocks that accelerate Madeline when she dashes through them. Each stage uses these specific objects to construct some fiercely challenging platforming scenarios. At various points, you'll need to squeeze through seemingly impossibly narrow gaps in obstacles, leap across crumbling platforms with atomic timing, and change direction in mid-air, sometimes more than once.

There's no question that Celeste poses a substantial challenge. There are individual screens which I must have attempted at least a couple-dozen times before succeeding. Importantly, though, Celeste doesn't simply drop this seemingly insurmountable challenge in front of you and walk away. It actively supports and encourages you through the process.

Some of this support is familiar. Celeste immediately respawns you at the start of your current screen, and autosaves after every screen, enabling you to walk away if you're really stuck on a particular stage and come back later without you being punished for it. Alongside this are direct encouragements from the game itself, telling you to be proud of your death-count, as it shows you're still trying, and advising not to go for the Strawberry bonus collectibles (which are placed in tricky-to-reach locations), unless you really want to. There's also an Assist menu which lets players activate powers to make the game easier, such as infinite dashes or even complete invulnerability.

This is all good and fine, but beyond its more optimistic outlook, I really didn't feel like there was much to Celeste that I haven't seen done before, while some aspects of its design are rather scattershot in approach. The art, while undoubtedly vibrant and pretty, isn't stylistically consistent. The menu-screen is a three-dimensional representation of Celeste mountain, the core game is pixel-art, and the dialogue screens imitate Japanese interactive novels.

I also found Celeste to be unbearably twee at times. The character designs, the appearance of the bunny-ears selfie trope, the dreadful 'Wowowowowow' noise that characters make when they talk, it's cutesy to the point of being nauseating, and I feel like these overly quaint stylings only serve to infantilise a story about adults attempting to function and thrive in the face of serious personal struggles. On a similar note, the chiptune soundtrack, which has apparently won awards, is rather obnoxious. At times, its gratingly loud bleeps and bloops set my teeth on edge.

The main issue, however, is that Celeste doesn't do enough to escape the whole “Pixel Platformer but X” problem. The base mechanics are virtually identical to every other jumping game, with few surprises or invention beyond the one or two new challenges each stage revolves around. If you're thinking ,'Well, if you don't like it, don't play it,' I get that. But the reason Celeste piqued my interest was because it looked like it might be different. Sadly, those differences are mostly skin deep, focussed on theme and structure rather than innovation at a deeper level. Like I said, pixel-platformer but X.

I appreciate Celeste's ideas, particularly the reframing of its challenge from cold elitism to warm encouragement, but I found its execution too saccharine for my tastes. I also would have liked to see it explore this notion at a deeper level, perhaps offering mechanical support to the player as a core part of the game, rather than sidelining it in a menu. There is some merit in Celeste's allegorical ascent, but I nonetheless feel like I've climbed this route many times before.

MSI MPG Velox 100R Chassis Review

October 14 2021 | 15:04

Want to comment? Please log in.