Price: £49.99

Developer: From Software

Publisher: Activision

Platform(s): PC, PS4, Xbox One

Version Reviewed: PC

If I was commanded at sword-point to summarise Sekiro: Shadows Die Twice in a single aspect of its design, then I would ask you to consider the Mikiri Counter. This manoeuvre, unlocked early in the game, enables our dogged shinobi Wolf to gracefully riposte thrusting attacks. This you do by standing in range of your enemy’s thrust and pressing the dodge button at the moment of their strike. If timed just right, Wolf will step nimbly to one side and plant his foot on the flat of your opponent’s blade, driving it to the ground.

Time it wrong, of course, and you will be brutally, often fatally stabbed. Such risk/reward-based battling has been part of From Software’s games since the days of Demon Souls. Unlike earlier entries, however, the Mikiri Counter is not some obscure ability that will be mastered only by advanced players; it is a basic skill, fundamental in every player’s combat retinue.

If that sounds daunting, well, I won’t say that it shouldn’t. Viewed from its base, Sekiro seems like an impossible mountain to climb. Despite its initial appearance, however, Sekiro is not designed to intimidate. Rather, it’s designed to make you feel unstoppable.

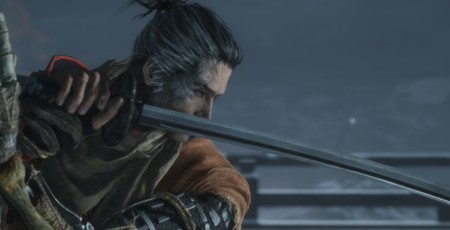

Sekiro places you in the role of Wolf, a shinobi who is bound to protect a juvenile lord named Kuro. Early in the game Wolf is left for dead after a battle that results in the severing of his left arm and the kidnapping of his liege. He awakes in the care of an elderly craftsman, who replaces Wolf’s missing arm with an intricate prosthetic, equipped with a grappling hook and space for further upgrades.

From here, you commence an adventure that has a familiar structure but a very different tempo. Sekiro’s world is built according to the same template as Dark Souls and Bloodborne. The world is large, mysterious, and cleverly interconnected, while Wolf can rest and improve his abilities at Buddhist Sculptures (which, in time-honoured fashion, will also respawn the majority of enemies you’ve killed).

Yet Wolf moves through this world with remarkable speed and agility, able to sprint through entire areas in seconds and traverse huge distances using his grappling hook. Meanwhile, Wolf is as light on his feet as he is fast, able to sneak, hide in foliage, and instantly kill enemies from behind.

Sekiro places greater emphasis on thinking tactically about engagements. You can just rush in and start attacking if you wish, but you can also scout out areas beforehand, then use stealth and your grappling hook to quietly dispatch as many enemies as possible before the alert sounds. You can even stealth-attack certain mini-bosses, making them much easier to deal with. Apparently, Sekiro started out as a successor to the Playstation stealth series Tenchu, and while in its final form it bears closer resemblance to From’s previous work, that secondary heritage remains evident in its design.

Inevitably though, stealth is only a mitigating tactic. You’ll regularly need to fight enemies from the front, and I really do mean from the front. Sekiro isn’t a game where you circle timidly around a gigantic boss, nibbling away at their backside like some heavily armoured parasite. You defeat your enemies face-to-face, turning away their blows and stepping on their thrusts, before punching a fatal hole in their bodies with your sword.

Central to this is Sekiro’s Posture system, which replaces the stamina bar from previous From games. Attacking enemies and deflecting their blows fills their Posture bar until their guard eventually breaks, opening them up for Wolf to deal a Deathblow, sinking his blade deep into their flesh and then yanking it out in a startling fountain of blood.

This system is wonderful in all sorts of ways. For starters it more authentically represents how deadly edged weapons are. Instead of essentially whacking your opponent with big metal sticks, each fight builds to a climax where you break their guard for that final killing strike. Both Wolf and his opponents still have health bars, incidentally, but health here is far less significant than Posture, as represented by their relative prominence in the UI.

More importantly, it is Posture that makes Sekiro’s major encounters so thrilling. Bosses regain their Posture quickly, which means you cannot hit them a bit, back off, and then wait for another opening. Instead, you create that opening by getting in their face, forcing them on the defensive, then further weakening their guard by deflecting and countering their own attacks.

This is undoubtedly the hardest part of understanding Sekiro, learning to stand fast when all your senses are screaming at you to flinch. Sekiro’s bosses are just as powerful and tricky as anything in Dark Souls or Bloodborne, whether it’s an enormous bull that charges at you with flaming horns, or a giant, spider-like enemy that thrashes at you with wolverine-like claws. Your instinct is to put as much distance between you and these monstrosities as possible. But if you stand still, focus, and time your blocks just right, you can deflect anything, be it arrows, bullets, or the horns of a massive bull.

Figuring this out isn’t easy – a few Sekiro bosses have given me a hard time, but when you finally overcome that instinct to flee, every new encounter stops being frightening and instead becomes exhilarating. Sekiro does help you out a bit with a couple of new mechanics. Most notably, death in Sekiro is not necessarily the end of a battle. Wolf can resurrect himself on the field at least once, and sometimes more. Also, the more challenging an encounter is, the fewer obstacles Sekiro places between you and it (and those bosses which have preceding obstacles usually offer a shortcut to get around them).

Combined, this essentially is From Software giving you permission to be bold, to throw yourself into a fight and master your opponent rather than simply avoiding them. This makes fights enormously gratifying as you deflect a seemingly impossible flurry of strikes or turn aside a hail of arrows. It also makes fights fast. It’s possible to overcome monstrous-seeming enemies in minutes, even seconds. One encounter that occurs at the climax of the game’s first act was such a thrilling sword fight that I genuinely didn’t want it to end.

The Posture system is the mechanic you’ll need to be most familiar with, but really it’s only the surface of Sekiro’s depth. Your prosthetic arm can be equipped with a whole range of different gadgets that let you tailor your fighting style to specific enemies. You can shatter shields into splinters with the loaded axe, while the loaded spear lets you draw distant enemies close and even yank pieces of armour from their bodies. There are also multiple skill-trees that gradually unlock as you progress, letting you learn a whole suite of new skills to enhance both your combat prowess and your stealth. A couple of favourites include the Anti-air Deathblow, which lets you instantly kill any enemy in mid-air (useful for several opponents that like to try to dazzle you with their acrobatics) and the Bloodsmoke Deathblow, which lets you disappear in a cloud of red mist that emanates from an opponent after backstabbing them.

That depth isn’t purely mechanical either; From’s representation of a mythical feudal Japan is just as complex and mysterious as you might expect. While the game’s opening is fairly linear and po-faced, the world soon opens up, transporting you to increasingly strange and haunting places and introducing you to a multitude of quirky and colourful characters. These range from morally questionable merchants who seek to profit off the destruction of war, to fellow warriors making their own way through Sekiro’s vertiginous, dangerous world. Each of these characters has their own quest-line to unravel, and rewards that change depending on how you resolve their stories.

More generally Sekiro’s mythology meditates on Buddhist notions of immortality, and how the pursuit of a corporeal immortality rather than a spiritual one has corrupted Sekiro’s world. Sekiro is narratively less opaque than previous From games, providing you with an easy-to-follow central plot (as well as remarkably clear instructions on how to play), but the secondary narratives will take players hours to unpick, while the broader themes offer plenty of philosophical quandaries to chew-over.

Problems wise, I find little to complain about, although I think the decision to bind your prosthetic abilities to a form of ammo (called spirit emblems) is a mistake, as it discourages experimentation in a game that already has a low tolerance for error. I also found myself forced to bounce between shrines too much in the mid-game, constantly having to return to multiple areas to upgrade different equipment. This damages Sekiro’s flow, making the shifts from one environment to the next less significant than they deserve to be. The world is interconnected in some impressive ways, but compared to Dark Souls and Bloodborne, these pathways are used much less often.

Also, there is no multiplayer component to Sekiro. No invasions, no summoning, no little notes left by players in parallel universes to your own. The reason for this is, again, that Sekiro wants you to figure out how to fight its bosses and solve its puzzles, but it does make the game a lonelier experience, and it loses the eerie quality brought by the spirits and bloodstains of Souls. Sekiro is strange in its own way, of course. But it is nevertheless the one aspect of From’s previous work that I genuinely have missed.

From a mechanical perspective, I think Sekiro is comfortably From’s best work to date. I don’t like to use the word 'addictive' as a complement with games, as I don’t see addiction as any kind of a good thing. Nonetheless, Sekiro’s combat is unbelievably intoxicating, and I’ve come out of many of the bigger encounters shivering with adrenaline. As for whether it’s From’s best game more generally, that’s a harder question to answer. It takes time to truly plunder the depths of From’s world building and mythology, time that Sekrio hasn’t enjoyed yet.

I will say this, however. Returning to that notion of the spiritual versus the corporeal, I’ve seen people claim that Sekiro is nothing like Dark Souls, and that people who go in expecting a Souls-like may be surprised and, perhaps, disappointed. But that’s only if you make a skin-deep comparison. In a spiritual sense Sekiro is exactly From’s fantasy masterpiece. Dark Souls tore up the rulebook that had been established over the previous decade and forced players to master a new set of rules. Sekiro is doing the same thing; it’s just the rulebook it tears up is the one established by Dark Souls.

It’s that spirit of renewal which binds all of From’s games together. The point is not the difficulty or challenge but the learning and mastery that stems from them. Sekiro may be an uncompromising teacher, perhaps the most uncompromising of all of From’s children. But the rewards of attending its school of hard-knocks are like nothing else I’ve experienced.

MSI MPG Velox 100R Chassis Review

October 14 2021 | 15:04

Want to comment? Please log in.