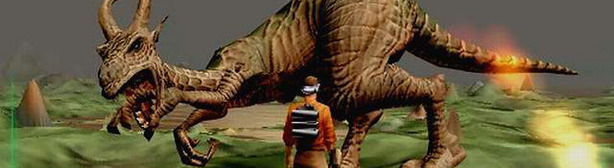

Outcast – 1999

Status: Available, but uncommon - try eBay.Outcast was a game that was massively hyped on release but which managed only moderate sales despite critical acclaim. It also deserves a nod for being the game with arguably the most fleshed out and established back-story ever.

A third person action-adventure set on an alien planet, players take over Cutter Slade – a US Navy SEAL sent as protection for a team of two scientists and a linguist on a journey to an alien planet. The four-man team has a simple enough mission – save the world from a black hole that formed as an unintended side effect when an experimental inter-dimensional probe was damaged in an alien universe.

Footage from the probe showed that an alien freaked out, shot the probe and caused an energy backlash which now threatens to devour the solar system. Cutter and Co. go through the dimensional rift to gather together the remains of the probe so that the energy disruption can be reversed. All in a day’s work...

Unfortunately, there’s a hiccup in the plans and Cutter is separated from the rest of his team. Kauffmann, the scientist in charge of the expedition is lost completely, mathematician Anthony Xue is captured by a fanatical tyrant called Fae Rhan and the linguist Marion Wolfe is taken underground by Fae Rhan’s pacifist opposers. It’s all south of FUBAR and Cutter is left desperately trying to put the pieces back together.

Outcast was one of the first games to blend so many genres together so seamlessly. On the one hand the game is clearly a third person shooter, but at the same time it has RPG, adventure and platforming elements. The player can take on side-missions from the native population, complete main missions in a number of ways, upgrade weapons and skills and explore the six unique ecosystems of the planet in any order they wish thanks to a free-roaming game design.

The theology, fauna and language of the alien creatures that the player interacts with during the game were enormously detailed too. The game even went so far as to introduce an automatic lexicon which monitored what alien phrases the player overheard and what their probable meanings were – expanding on descriptions and translating as the game moved ahead.

Most astounding of all though was that the game did all of this in rather stunning 3D, despite using a graphics engine which relied solely on putting voxels together. The result was incredibly CPU intensive at the time, but hardly a problem nowadays and there are several patches to help players run it today.

Planescape: Torment – 1999

Status: Available, and common - try eBay.I didn’t play Planescape: Torment when it first came out because I was still far too engrossed in Black Isle’s other RPG classic, Baldur’s Gate II: Shadows of Amn. When I did finally track down a copy of Planescape: Torment it was sat in a pound shop boxed with two or three other games. I bought the whole lot for a song in what was probably the best investment I’ve ever made.

Planescape: Torment is set in the oft-forgotten D&D Planescape setting and has some superficial similarities to other Black Isle RPGs. In reality though, Torment stands apart from Baldur’s Gate and its ilk as perhaps the most insightful game you’ll ever play.

It starts off weirdly – you are The Nameless One, an immortal amnesiac who wakes up in a mortuary and sets out to discover who he is. Gameplay is radically shifted from the usual paradigms because of the nature of your character – you can only die in the few situations where your body is utterly destroyed, so combat is never really a threat to you.

The focus of Torment therefore lies elsewhere – in conversation and inter-character relations. Frankly, if you thought Mass Effect had well-developed characters then you haven’t seen anything yet. Your allies and foes in Planescape: Torment are intricate beings who come from all kinds of origins – a floating skull from the depths of hell, a Githzerai monk who wields a blade of chaos-matter and a chaste Succubi who runs a whore-house.

The thrill and genius of Planescape: Torment doesn’t lie in the action or the quests – but in the truly fluid nature of the player character and his demeanour. There is no conventional class-choosing or levelling up – it’s just a matter of finding someone to teach you. When you undertake a quest you can choose not just your response, but also the emotion behind the response – do you truthfully vow to find the lost child?

Do you falsely make the pledge, shrug non-committedly or openly say you don’t care? Each action and reaction explores your character more, marking the game as more of a personality simulator than an RPG – and one we can’t recommend highly enough for any genre fans bored of countless Final Fantasy re-runs.

MSI MPG Velox 100R Chassis Review

October 14 2021 | 15:04

Want to comment? Please log in.