Revisited: Alan Wake

August 15, 2019 | 13:39

Alan Wake was a stupid game pretending to be smart. It’s the world’s most hackneyed third-person shooter dressed in a duffel-coat and an overwhelmingly unearned sense of its own importance. I found its writing lumpy, its characters hard to like, and the gap between its thematic ideas and mechanical execution the epitome of the phrase “ludonarrative dissonance”.

That’s what I thought when I first played it. I disliked Alan Wake so intensely that I’m still not sure why I decided to go back to it. Remedy’s upcoming action-adventure Control was the trigger for returning to a title from the studio. But there are several other games I could have chosen, like the more recent Quantum Break, or either of the Max Paynes (both of which rank amongst my favourite games).

Why then, did I choose a game that I know I don’t like? That I think is a bunch of pretentious twaddle wrapped around a mediocre shooter. Frankly, I think that is the reason, at least in part. See, I know I didn’t like Alan Wake when I originally played it, but that was almost ten years ago. A lot can change in a decade. For all intents and purposes, the person who didn’t like Alan Wake back then may no longer exist.

So, over the last couple of days I’ve been back to Bright Falls, seeing the sights, smelling the air, licking the paintwork. And you know what? By the time the credits rolled, I didn’t want to leave.

Don’t get me wrong, the flaws of Alan Wake are still as plain to see as the game’s own Mirror Peak. The writing still veers from passable to cringeworthy. Mechanically the game is a grab-bag of features that never quite fit right. Alan still has his writerly head stuck in his large intestine. Bright Falls hasn’t changed at all. But I have.

Even before its release, Alan Wake was clearly a troubled project. The game was in development for five years, delayed several times, and changed significantly over the course of that period. Most importantly, it was originally planned to be an open-world game, but was altered to be a linear, narrative-driven experience. The scars where that open world was removed are still plain to see. They’re in the driveable cars that appear for short sections of the game, mechanically functional but serving no real purpose, and in the town of Bright Falls itself, clearly designed to be explored freely, but never giving you the chance to do so.

When I first played Alan Wake, all I could think of was the wasted potential of the world Remedy had designed. Imagine if you could walk the streets of Bright Falls freely. Imagine if you could take a car up into the mountains and explore at your own pace? This was at the time when open-world games were just coming into vogue, and Alan Wake’s rigid linearity seemed like an outdated design.

Now of course, we’ve been gorging on them for years. I don’t know about anybody else, but these days I’m the open-world equivalent of Mister Creosote, one cookie-cutter side-quest away from exploding. Rather than being appealing, the idea of a 30-hour-long, open-world Alan Wake makes me feel downright nauseous. Indeed, going back to Alan Wake, I found its dedicated linearity and relatively brief running time to be a refreshing change of pace.

What helps is that the one thing that was always good about Alan Wake – its sense of atmosphere and place – still holds up. Bright Falls remains a wonderful location to explore – still the closest we’ve come to a virtual Twin Peaks. Most of the game takes place at night, but I love the little daytime interludes where you get to poke around the police station or the trailer park, or Doctor Hartman’s rehabilitation clinic for artists.

I also appreciated how well structured the night-time action is. The way each chapter illuminates your objective in the distance, be it a gas station or a radio tower or a power plant, and how it manages to find so much locational variety in the backwoods of the Pacific Northwest, taking you down abandoned coal mines, through old trainyards, dilapidated farmsteads, The way it keeps changing the scenery across 14 hours of play, while maintaining a natural look and feel to the landscape, is genuinely impressive.

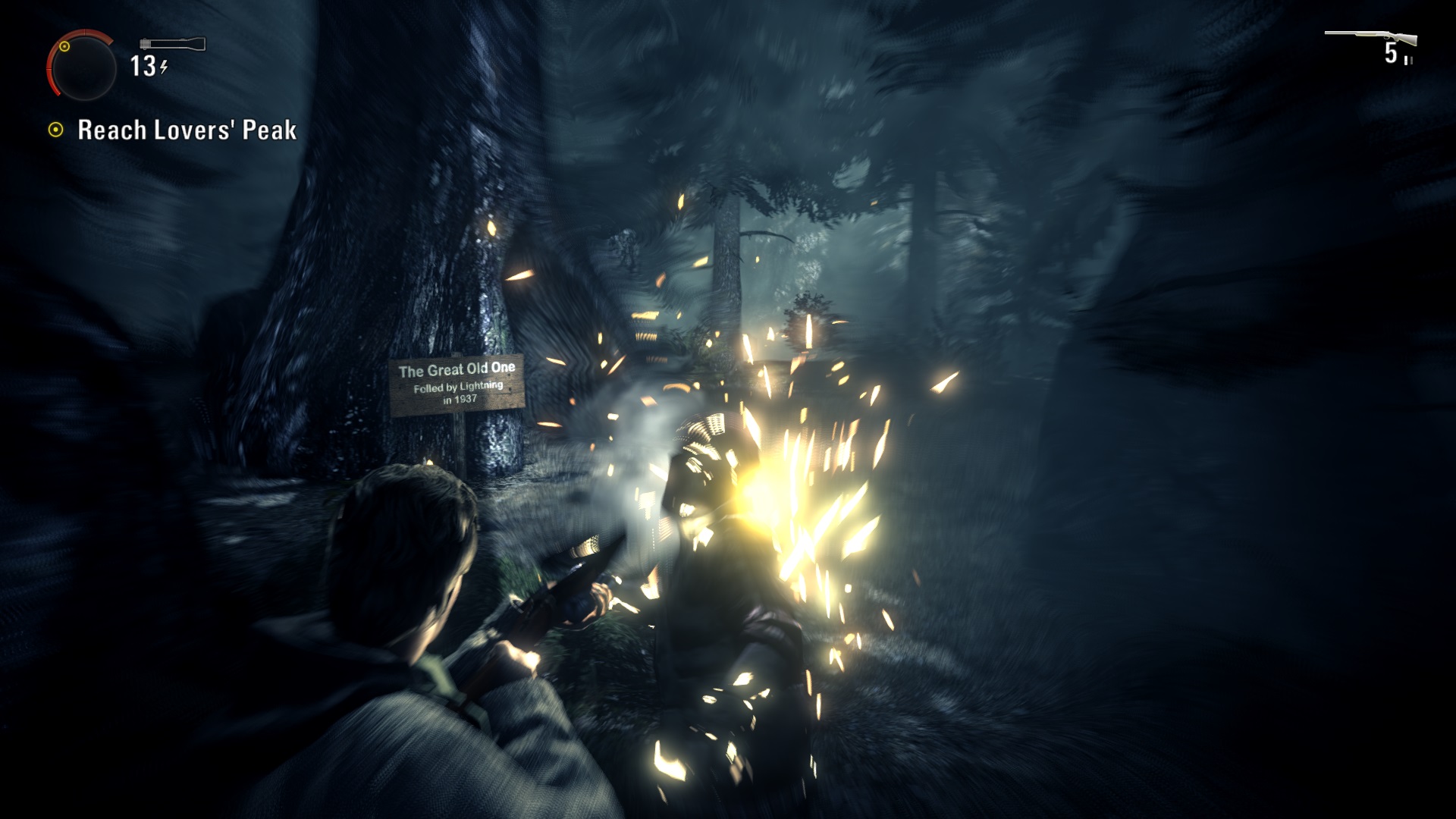

Combat, too, holds up better than I remember. It’s still no Max Payne, but there is something satisfying about the one/two punch of dissolving an enemy’s darkness-shield with the flashlight and then blasting them with a gun. I also love the way the game portrays light and darkness, giving both a rich and tangible texture. The way the darkness seems to literally seep through the forests, and how lights soak any surface they touch, acting like a liquid barrier against the night. It’s exceptional visual design that retains its power a decade on.

What was most fascinating, however, was how I appreciated the story from a very different angle. Alan Wake is obviously a game about creative frustration. Alan has a case of writer’s block so bad that it literally begins to destroy the world. But what I didn’t understand at the time, and what I appreciate now, is that Alan Wake is specifically about Remedy’s own creative frustrations making Alan Wake.

This is described brilliantly by another critic - Rob Zacny – in his 2011 article that breaks down Alan Wake’s own torturous creation, and Remedy’s in-built reflections on it. Zacny writes “From its opening scenes, Alan Wake is a chronicle of creative frustration and insecurity. The game opens on a dream in which Wake is hunted by a deranged hitchhiker. As the hitchhiker pursues Wake toward a lighthouse, he screams, "It's not like your stories are any good! It's not like they have any artistic merit. Cheap thrills and pretentious shit. That's all you're good for.”

I thoroughly recommend reading the full article, especially if, like me, you plan on returning to Alan Wake prior to the launch of Control. It doesn’t change the fact that Alan Wake’s story is completely bonkers and often poorly delivered. But it helps clarify why the story is so bizarre, and helps you see where the story succeeds at a metafictional level, even while its failing at a plot and character level

Rather than being a game obsessed with its own self-importance, Alan Wake is in fact riddled with doubt about its own worth, desperately trying to do something more with established video-game conventions, and becoming increasingly fraught at its own failure to do so. This doesn’t improve the end quality of the game itself – far from it. But in its running commentary upon its own creative struggles, it does make Alan Wake one of the most fascinating games ever made.

MSI MPG Velox 100R Chassis Review

October 14 2021 | 15:04

Want to comment? Please log in.