Price: £15.49 Inc VAT

Developer: Lucas Pope

Publisher: Lucas Pope

Platform: PC

Return of the Obra Dinn is the best detective game ever made. The year is 1807, and the cargo ship Obra Dinn has drifted into the Bay of Falmouth after being lost at sea for four years. The ship’s crew and passengers, sixty souls in all, are missing.

You play an insurance investigator for the East India Company, immediately dispatched to Falmouth to prepare an “assessment of damages”. From this simple beginning, Return of the Obra Dinn spins a strange and utterly captivating tale of oceanic tragedy, one that sees you piecing together the fate of its crew through an open-ended puzzle that requires proper deduction to solve.

While your official objective is to assess the state of the ship, your goal as the player is more specific. You need to determine the fate of every crew-member who departed England five years prior, identifying which crew-member is which, and then figuring out what happened to them.

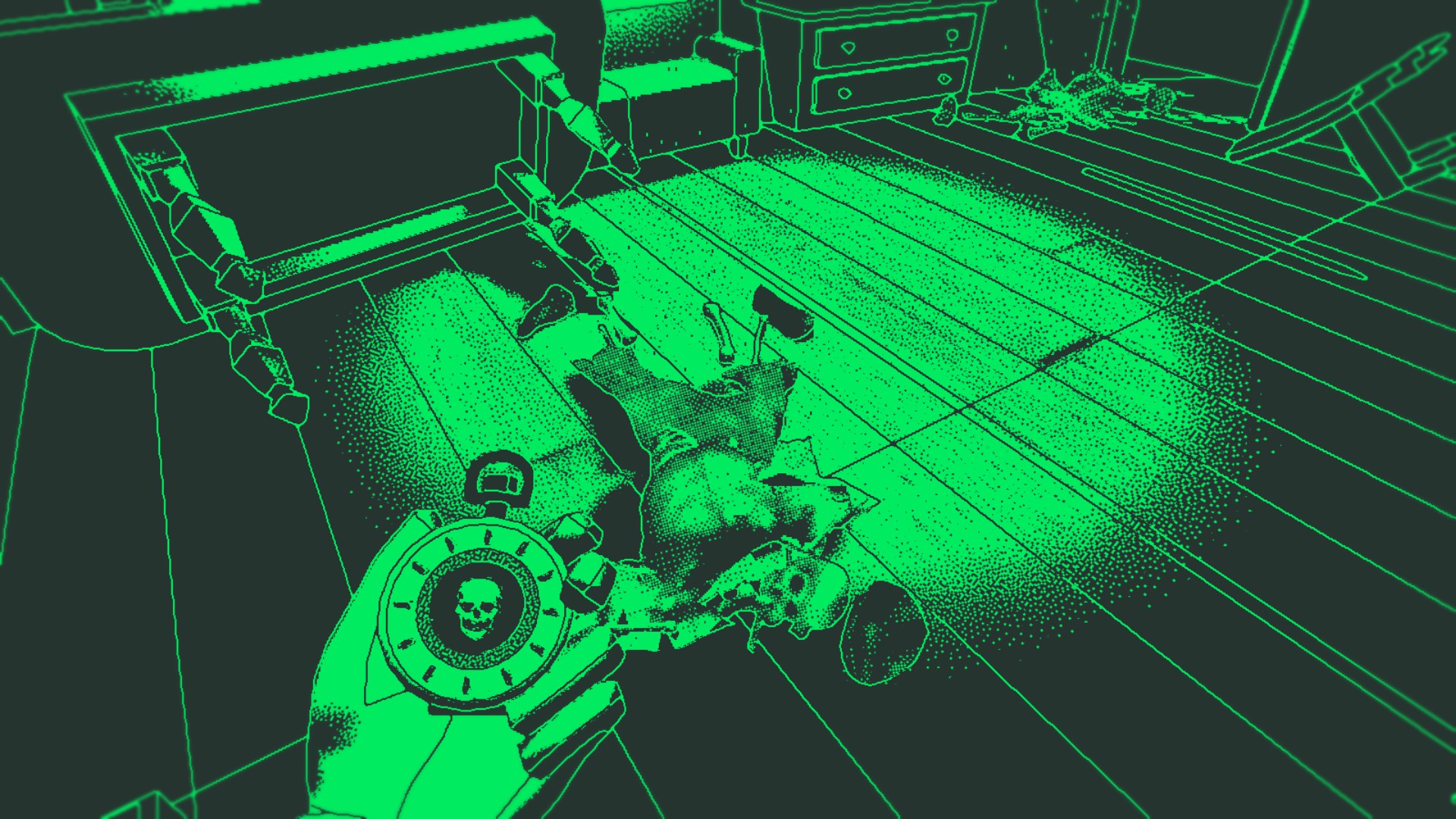

Given there were 60 souls on board, it’s a substantial task. Fortunately, when you first board the vessel you’re given two pieces of equipment that will help you solve the mystery. The first is a pocket-watch engraved with the image of a skull, which allows you to access “memories of the deceased”. Once on deck, you’ll quickly stumble upon skeletal fragments of the crew. Clicking on these bones with the pocket-watch in your hand will transport you back to the moment of that person’s death.

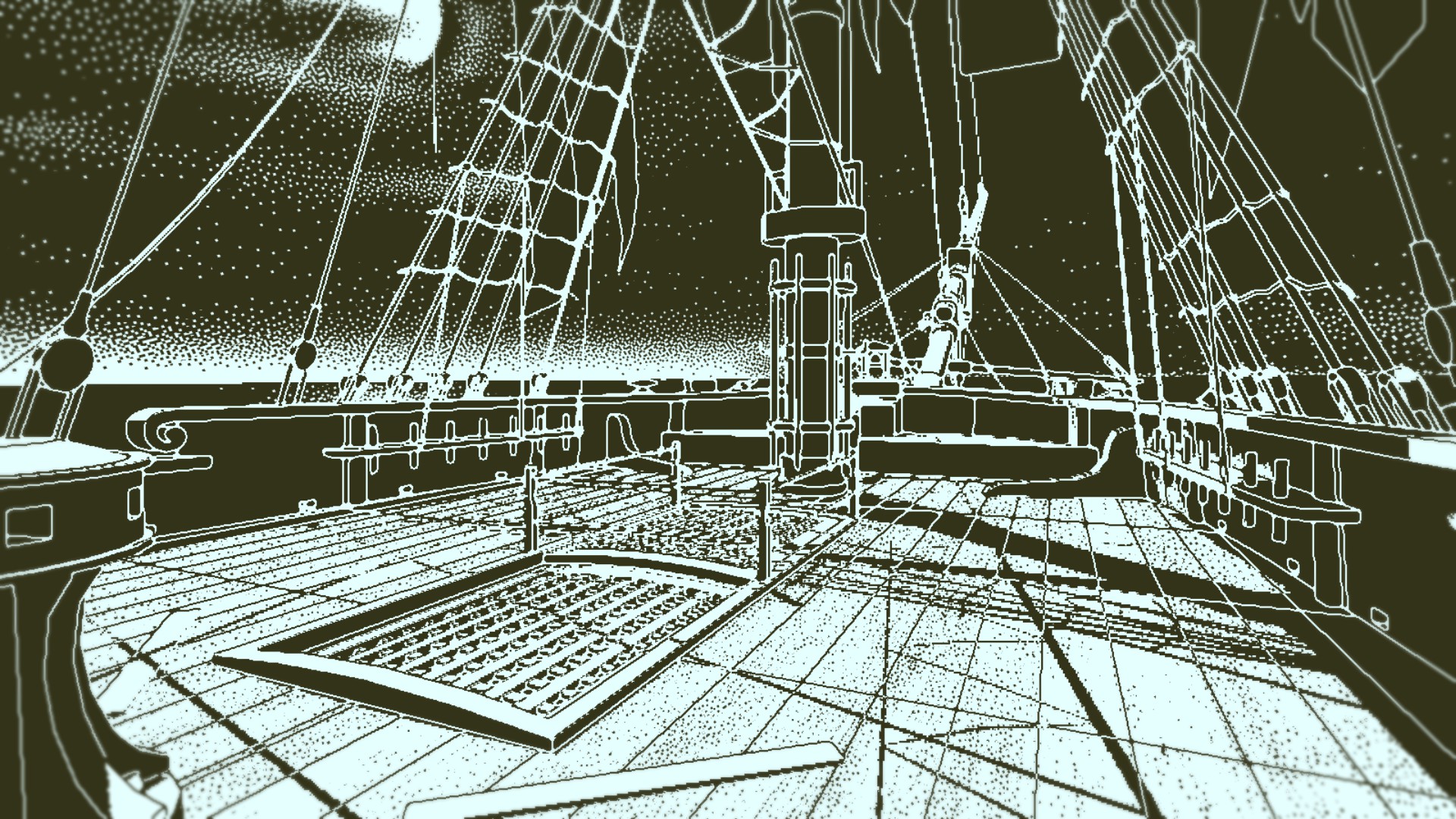

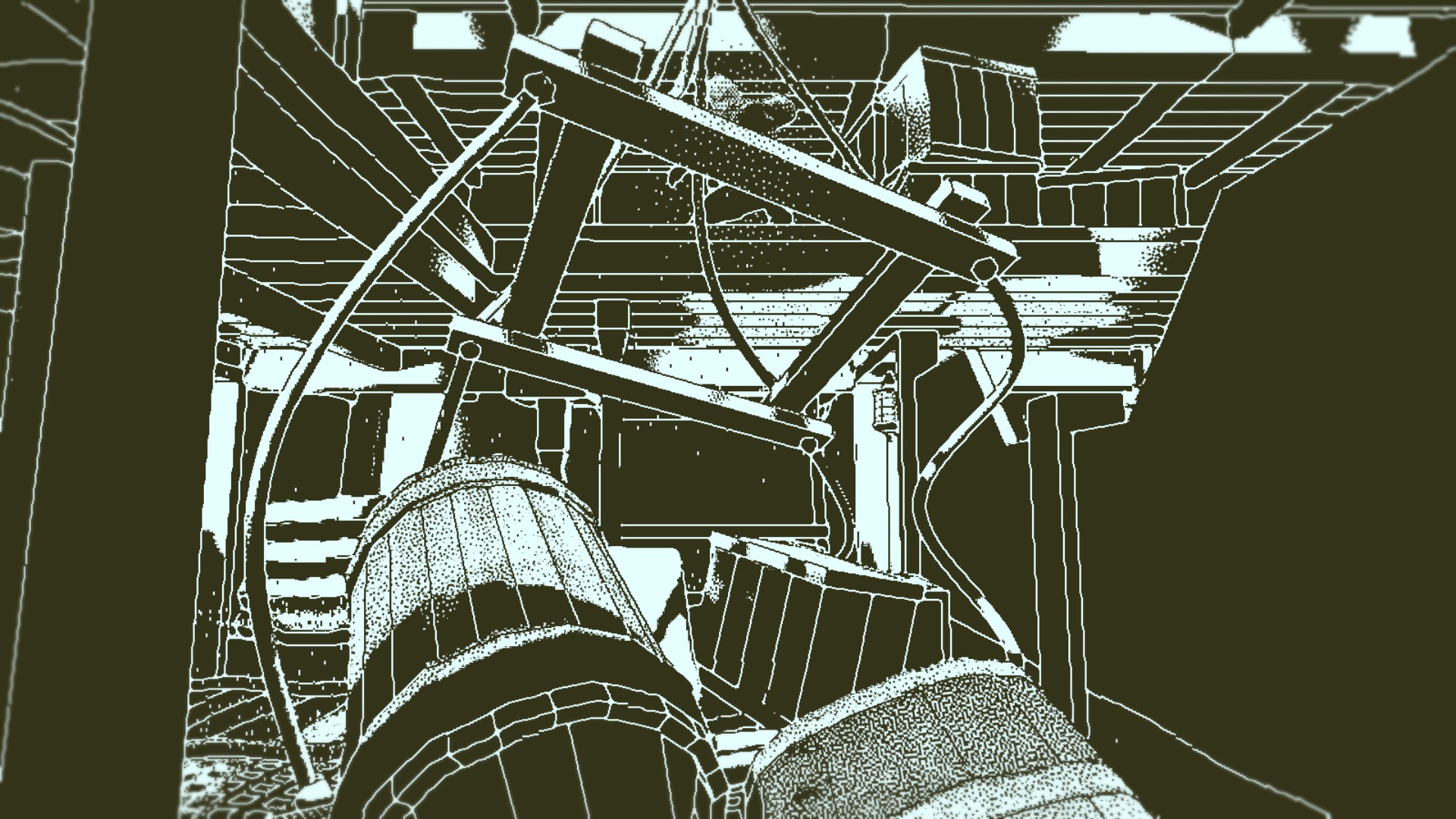

Within these memories, the dead come to life, albeit still-life. You appear within a static snapshot of the ship’s past, taken at a key moment (often but not always to do with the death of a crew-member). You’re able to move freely exploring the ship in that moment, searching for clues to help you unravel the ship’s many mysteries. Meanwhile, the sounds of the ship fill your ears, the creaking of the ship’s hull, the wash of the waves, the noises of the crew chatting, yelling, and scrambling into action.

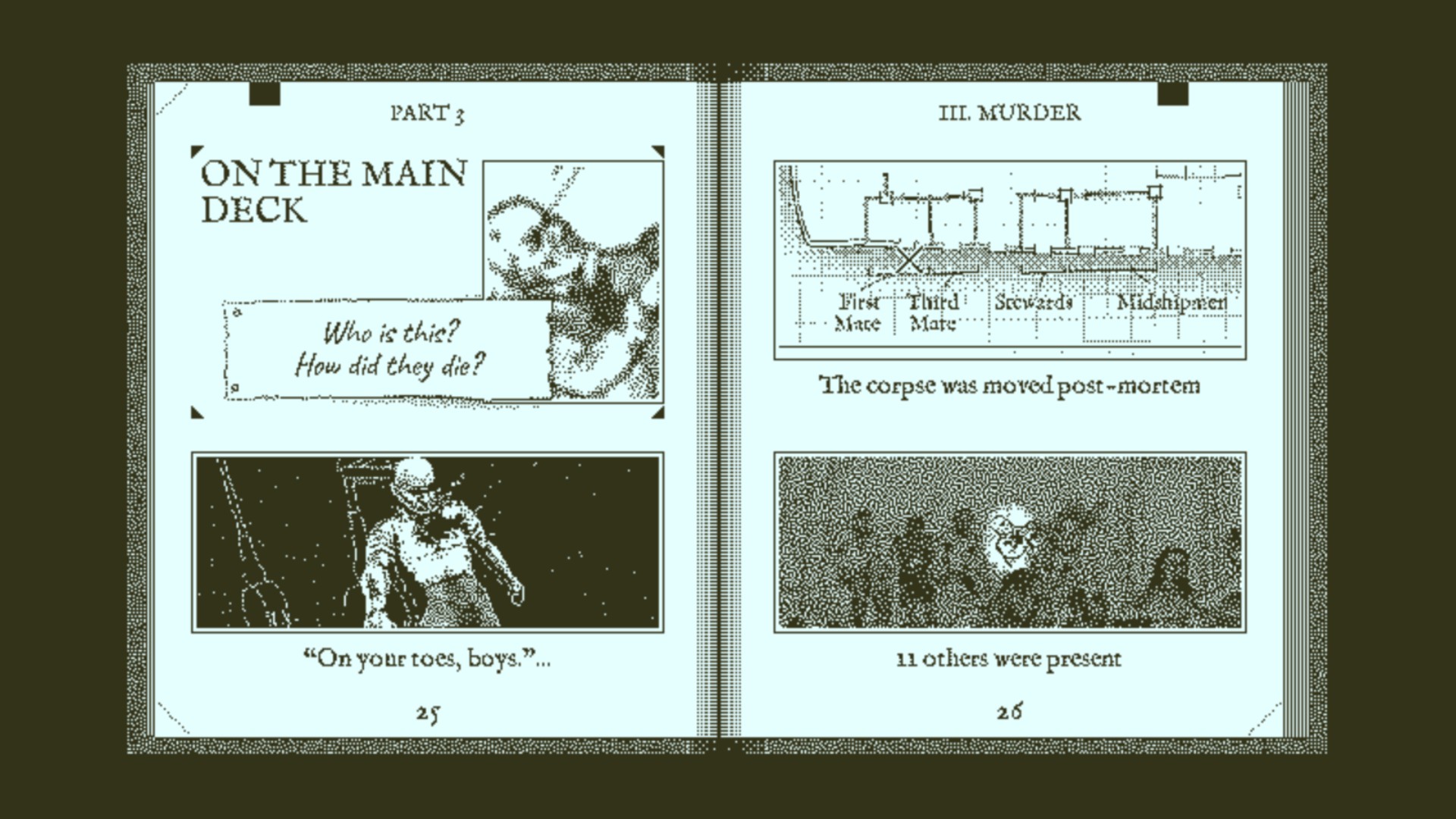

Your supernatural time-piece isn’t the only tool at your disposal. You also have access to a logbook, which divides the fate of the ship into a total of ten blank “chapters”. With each new memory you explore, the book fills in a couple of pages dedicated to the crew-member at the centre of the scene. Once you uncover their identity and their fate, you can write that information into the book. The book also includes several useful documents, such as a full crew manifest, and several sketches of the crew on deck.

Although the central mystery of the Obra Dinn always remains the same, how you come to deduce the identity and fate of each crew member is entirely down to you. The fates are often the easiest to deduce, given most scenes are centred around how each crew member either died or disappeared. Putting a name to each face, however, is considerably more challenging. Occasionally, you’ll get lucky and one character will refer to another by name in dialogue. But more often you’ll need to work it out for yourself, looking at how each character is dressed, listening to their accents, or tracing their route and activities on the ship to figure out their role on board.

Unlike nearly all other detective games, Obra Dinn requires true deduction. Outside of the information in the book and what you can observe in each memory, there’s no hinting, quest markers, or other out-of-context nudging done by the game. In fact, Obra Dinn actively discourages gaming the system. To prevent players from brute-forcing solutions, the game only reveals correct solutions in groups of three, which are then set into the logbook in type. This means you can’t just run through every name in the crew manifest with each individual.

This does have a downside, in that it can lead you to wrongly second-guess yourself when a solution you’re sure is right isn’t recognised by the game. But this is a far smaller problem than the one Obra Dinn solves, namely, to make a detective game that involves observation, logic, process of elimination, establishing timelines, and use of evidence to determine a conclusion.

Indeed, I don’t consider myself particularly good at puzzle games, but I figured out all but four of the fates and identities purely through the information provided by the game. In one example, I went back to a memory I’d visited before, and noticed a tiny detail in the environment that instantly led me to the solution in classic detective-fiction style. Meanwhile, the identity of the French Bosun’s Mate was almost my one that got away, a mystery I latched onto very early on and obsessed over for hours, only solving it toward the very end of the game.

Purely as a puzzle, Obra Dinn is a fascinating thing. But there’s so much else about this game that contributes to its brilliance. The art-style, which I wasn’t sure about at first, fits the game perfectly. Conveying a naval mystery through the 1-bit dithering of old MacIntosh adventure games works superbly, and actually contributes to the game’s period setting, like making a movie with black-and-white film. It’s worth noting that you can choose several old-fashioned monitor “output” styles, including the crisp green lines of an IBM 5151, and the purplish haze of a Commodore 1084.

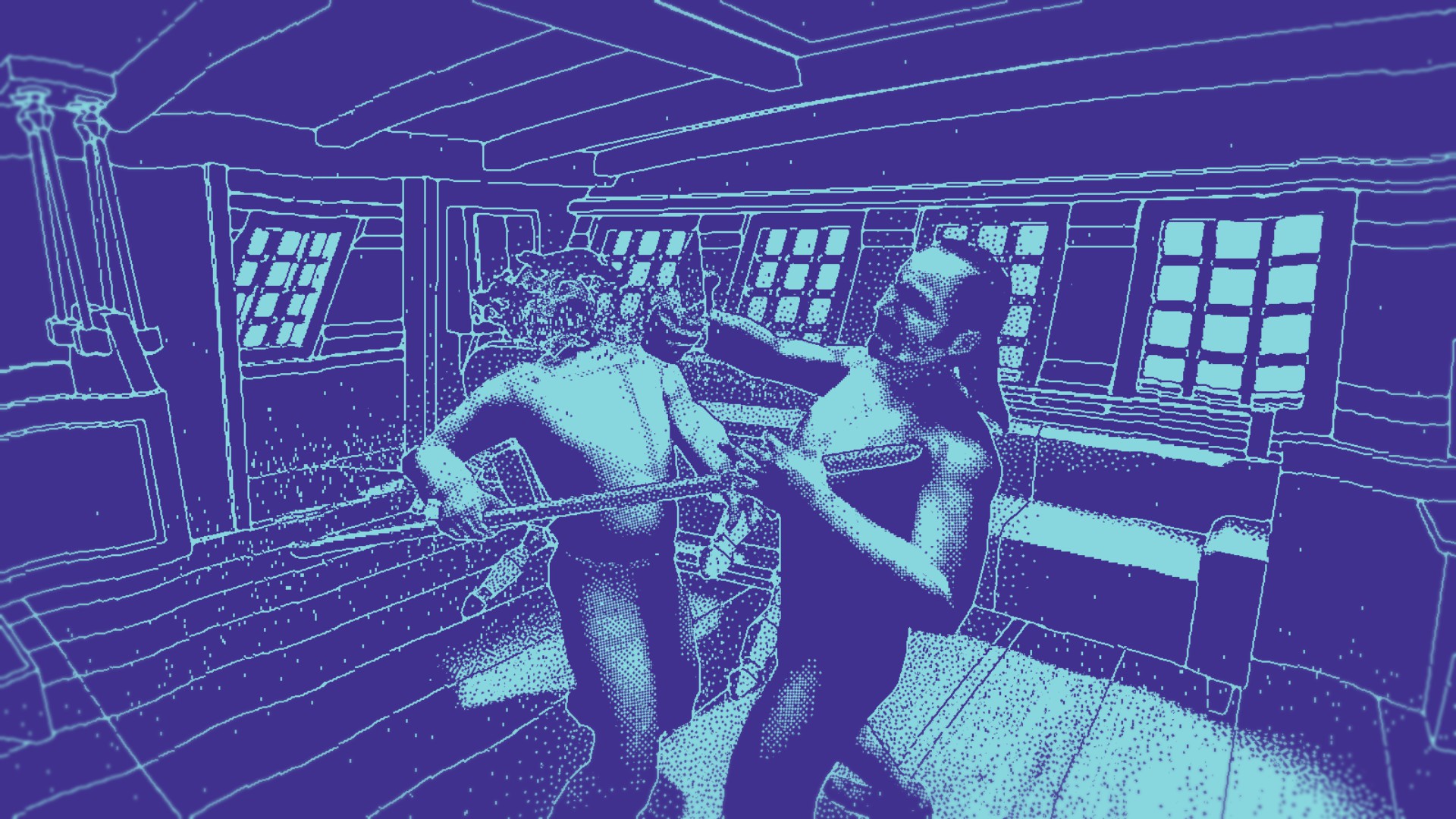

The “memory” scenes are stunningly choreographed too. Each is like a 3D panel from a graphic novel, conveying movement and action through careful posing of characters and objects. In a strange way, the lack of animation actually emphasises the horrific nature of the game’s violence. During the Obra Dinn’s last days, people are shot, stabbed, bludgeoned, exploded, crushed by loose cannons and falling cargo. The way each memory begins as a black screen, before cutting to the precise moment of death, is incredibly effective.

There are times when the relentless nature of the Obra Dinn’s catastrophe verges on the absurd, but despite the strange and borderline silly twists the story takes, the game always manages to maintain its credibility. A lot of work is done by the fantastic musical score. The curiously jaunty blend of cellos and carillons sets the tone beautifully, both in terms of period and overall mood. For all its death and calamity, Return of the Obra Dinn is never morbid, and there’s a slight knowing-ness to the score which encourages you to go with its more bizarre twists and turns.

There are a couple of areas where Obra Dinn falters. The voice acting, while for the most part fine, does betray hints of amateurishness. In particular, a few accents can be hard to decipher, especially problematic in a game where an accent can be the key to unlocking a person’s identity. Also, much as I love the art-style, it can make certain scenes difficult to take in. I’ve wrongly labelled several causes of death because I couldn’t clearly see what was happening.

None of these minor qualms prevents Return of the Obra Dinn from being my favourite game of the year so far. Exquisitely crafted, hugely innovative, and fascinating to the end, Return of the Obra Dinn is a testament to the artform.

MSI MPG Velox 100R Chassis Review

October 14 2021 | 15:04

Want to comment? Please log in.