Riddle me this, puzzle me that

Puzzles are the other primary element of adventure games and it’s these which form a lot of the challenge for gamers. Adventure games can obviously range in how heavily and dramatically they incorporate puzzles into games, but either extreme can risk upsetting players.Take The Hitchhiker's Guide to The Galaxy, for example. A fiendishly difficult game, the inventory included items like ‘that thing which your aunt gave you which you don’t know what it is’ and the infamous Babel Fish which could only be obtained from a Babel Fish dispenser. The puzzle around the dispenser was incredibly tricky though and neglected to inform the player that the game was utterly unwinnable if the puzzle was failed. You just muddled through until you met a dead end.

Is this how puzzles and challenges should be used in adventure games or should they be toned down to simple quizzes which effect the ending scenario but which don’t actually prevent gamers from playing, as in the DS’s Twin Memories: Another Code?

I wanted to put the question to both Davids and fine out how puzzles are designed and placed in adventure games, but first I wanted to know just what they thought the puzzles were good for. After all, both writers considered story to be the most important element of their games, so what about the puzzles which can, quite literally, stump players and stop them progressing through the plot?

I started by asking Dave Grossman about how puzzles were used to slow players down in adventure games and how he worked to placed puzzles in the world realistically. As it turned out I was already way off the mark and both Davids had a radically different idea of how puzzles and challenges are used in games – different both from me and from each other.

“I use the challenges in an adventure game to entertain players, to let them feel clever, and to let them drive the story forward, but I'm never really trying to slow them down,” said Dave Grossman, giving me an entirely different idea of how puzzles should be used. What I had originally assumed were placed in games to help lengthen the experience, Dave saw as being used primarily to heighten the fun.

“I think of adventures as a storytelling medium, and I don't want there to be too much dead space in the experience. I try to set up the puzzles to be just challenging enough that you'll be pleased with yourself when you solve them, but to stay short of the line of frustration.”

David Cage however had an entirely different view of the topic – one which fitted with his past games and how they often leave various options open to players.

“A game does not have to be a challenge at all, it can also only be an experience where you affect what’s going on, make decisions and deal with the consequences.”

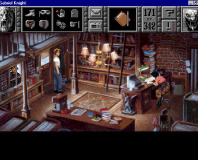

The later Broken Sword titles were heavily critiscised for using puzzles which were out of place in the game world

This fits almost perfectly with the previous example from Fahrenheit where players must choose how they choose to react to the murder they have just committed. There is no right or wrong solution in this scenario and players can choose to hide the murder weapon and body, clean the crime scene and leave quietly or they can bolt for the door and make a run for it. The whole scenario then plays across into the next scene where the detectives must make a choice about how thoroughly they want to search the area.

This style of puzzle shows that games can be written not just to involve challenges, but to present ethical dilemmas and options to the player, something showcased brilliantly in Facade, a freeware interactive drama which is perhaps best described as an indie adventure-drama. Cast as guests at a dinner party gone awry, players must struggle with emotional problems instead of logical ones.

“I try not to write puzzles as such, but to create contexts for choices, and I try to make them logical and to give them consequences. The player is then not in front of a puzzle but of a decision to make, which will help to move the story onwards,” David Cage said, outlining how puzzles can be avoided in favour of other solutions.

“I try to work on the fact that player’s decisions affect the outcome of the situation instead of making him succeed or fail. ‘Game over’ is not a satisfying state for players and I try to avoid it as much as I can... Very few games have really explored the possibility of using the story as a material by itself that the player can play with. Fahrenheit was my attempt in this direction, but there is definitely still a lot to explore.”

MSI MPG Velox 100R Chassis Review

October 14 2021 | 15:04

Want to comment? Please log in.