The game mechanics that should have changed the world, but didn't

August 23, 2019 | 10:30

Companies: #arkane-studios #bethesda #epic-games #microsoft #monolith-studios #sega #valve #volition #warner-brothers

Gaming is largely an iterative artform. Building a game is as much engineering as it is artistry, and a large part of engineering is the refinement of existing ideas. How many times have you played a game that sells itself as 'Minecraft but X' or 'Mario but Y'? How many times have you played a slicker version of Doom?

Of course, for an iterative artform to work, there has to be a Minecraft or a Mario in the first place, games that come along and suddenly shunt the genre forward in new and unexpected ways. There is no better moment in this job than seeing that happen the first time you play a Doom, a Minecraft, a Return of the Obra Dinn.

Sometimes, though, this doesn’t happen. Sometimes a game comes along that, by all rights, deserves to pave the way for a whole legion of followers, but for some reason those ideas never take off. You find yourself waiting for the next game to pick up that newly created baton, and yet it never comes along.

This is an article dedicated to those ideas, the mechanics that blew us away the first and, inexplicably, only time we ever saw them.

Nemesis System – Shadow of Mordor

Let’s start with the most obvious example, the Nemesis system from the excellent Middle Earth: Shadow of Mordor. One of the biggest problems with creating open-world games is balancing dynamic and bespoke play. You want your game to make the most of that open world with exciting, random events generated by the game itself, but you also want those systems to feel unique and player driven and not like they’re regurgitated or obviously procedural. So, inevitably, you end up putting in more hand-crafted stuff, which, ironically, makes the game less dynamic.

The Nemesis system is designed to solve this problem in two ways. Firstly, it gives what would otherwise be faceless enemies unique and memorable personalities through clever use of random generation. Secondly, it places those enemies in a political hierarchy that you need to manipulate and destabilise – essentially giving the player the power to create their own objectives.

It’s an enormously powerful system, and one of the best uses of an open-world format I’ve ever seen. When SoM launched in 2014, I was certain that every other open-world developer would soon produce their own version of the system, and was thrilled at the prospect. But it hasn’t happened at all. The only other game to use it is SoM’s own sequel.

I’m not sure why this is the case – perhaps the cost and effort of creating such a system simply isn’t worth it compared to other open-world designs, or maybe Monolith/Warner Bros know what they’re onto and have been careful revealing how the system works (although I’m sure it could be reverse-engineered). Either way, the revolution I expected in open-world gaming never happened, and I think the Nemesis system represents the genre’s biggest missed opportunity.

Active reload - Gears of War

I’m not the biggest Gears of War fan. I think the games are mostly fine but not much more than that. There is one area, however, where Gears of War shines above almost any other shooter, and that’s reloading.

It’s not an area of FPS games that gets examined very much, but reloading is an important component in FPS design. Not only is there the “cool” factor of it (which is quite odd when you think about it), reloading also has a big impact on the rhythm of an FPS. It’s a brief pause in the music, generating tension as you’re temporarily prevented from fighting, and building anticipation of what’s going to happen when combat resumes.

Gears of War adds an extra step to heighten that tension and anticipation. When you reload in Gears of War, a little side-bar appears at the top of your screen, with a small icon that scans across it. Press the reload button a second time when the icon is in the sweet-spot, and you get a temporary damage boost. Press it at the wrong moment, however, and your gun jams, forcing you to stay out of combat longer while Marcus fixes the problem.

It’s a tiny change, and yet it adds enormously to the ebb and flow of Gears of War’s combat. Your gun might jam just as the enemy advances, forcing you to retreat. But then when your next clip empties, you might get a damage boost and claw your way forward to your initial fighting position.

You’d think active reload would have appeared in every cover shooter since. Mass Effect, Uncharted, Binary Domain. Nope. Just Gears of War. It’s a particularly baffling one, as it’s a relatively simple concept that disproportionately improves the pacing of an action game.

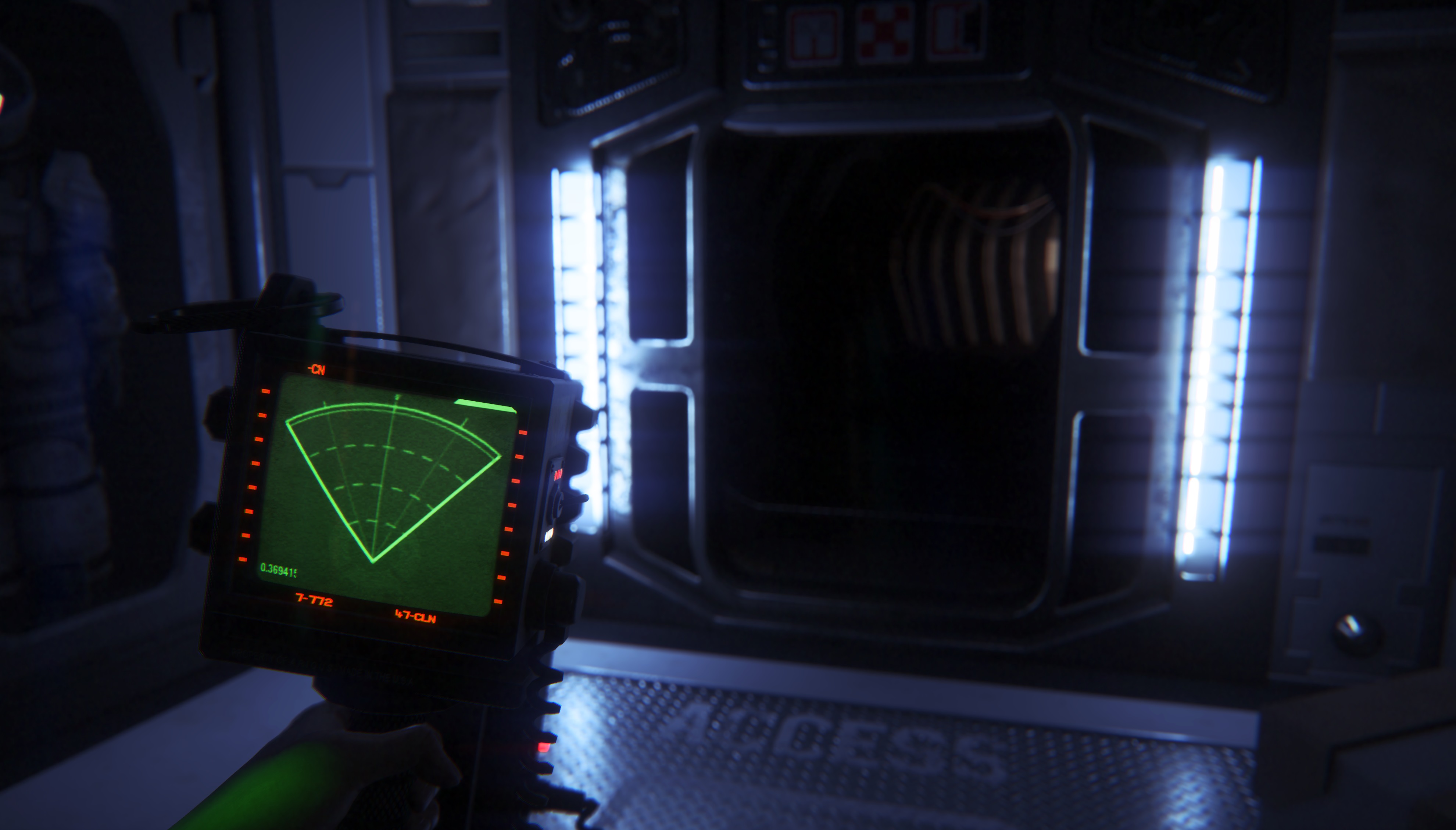

Persistent-enemy horror – Alien: Isolation

Five years on since it’s launch. Alien: Isolation remains my favourite first-person horror game. There are plenty of reasons for this. The incredible environment design and atmosphere, the compelling storytelling. Mostly though, it’s the incredible AI work built into the brain of Isolation’s Xenomorph, and how it produces the sense of being actively hunted by a predator that is as cunning as it is unstoppable.

Although I refer to this as a mechanic, Isolation’s Xenomorph doesn’t really function through a single, identifiable system. Rather, it’s a collaboration of art and tech that includes animation and environment design as much as it does programming. From a coding perspective, the environments in Isolations are as much your enemy as the Xenomorph itself, calling out the creature and telling it places where you might be hidden, so that it knows where to investigate, heightening the tension.

Nonetheless, this collaboration amounts to an identifiable feedback loop, where you’re chased through Sevastopol station by the creature, hiding in cupboards and under beds to avoid its deadly kiss. The potential of this structure is enormous, as so much horror is based around the idea of being stalked by an unstoppable killing machine. Imagine an open-world game where you’re stalked by a single Terminator, or a Ghost Recon-style shooter where the Predator occasionally rocks up to ruin your team’s day.

Unlike the previous two games, there are clear reasons why nobody has done an Isolation-style game. The first is, as I intimated, getting the Xenomorph to work in Isolation was really, really hard. Secondly, the game didn’t sell as well as Sega hoped, which is why we never saw a sequel. A couple of games have sort of explored this, such as Friday the 13th, but that involved a player stalking other players through match-based play and doesn’t have the clever AI systems and persistent atmosophere of dread that made Isolation such an incredible game.

Blink – Dishonored

The Dishonored series has more awesome mechanics than perhaps any other from the last decade. From the ability to possess guards to Dishonored 2’s incredible Domino power, which lets you link the fates of multiple enemies so whatever affects one will affect all of them.

But the most important and transformative power in Dishonored is also arguably its simplest – Blink. Blink is a short-range teleport that lets you phase forward about 10 to 20 feet through the air. You can use it to quickly cross a guard’s line of sight, or to access the upper floors and rooftops of building, which would be impossible for a normal person to reach.

Blink is such a well designed mechanic that it becomes a natural part of your movement within about five minutes of you acquiring it. In fact, it becomes so normalised as part of your explorations in Dishonored that going on to play a game without Blink feels like you’ve broken a virtual leg. Even Arkane itself couldn’t improve upon Blink, with Emily’s Far Reach and Meagan’s grappling hook being ultimately inferior adaptations of the same idea.

Blink has sort-of appeared in a couple of other games. 2014’s Thief reboot had a “swoop” mechanic which was a version of Blink limited to the ground, and I’m fairly sure Deus Ex: Mankind Divided included a Blink-based movement system too. But that’s not enough. I think every immersive sim should have its equivalent of Blink in the same way that every immersive sim since Thief has featured a stealth system. Heck, you could put Blink in every game from an FPS to a Kart Racer, and there’s good chance it’d improve the experience.

Destructible Buildings – Red Faction: Guerrilla

How this one didn’t catch on I’ll never know. Did Red Faction: Guerrilla secretly sell really badly, or did everyone just sleep through the year 2009? In fact, stop reading this article. Stop right now. Go and boot up Red Faction: Guerrilla, hit something with a hammer, and think about the fact that no other game in the last 10 years has used its destruction mechanic.

Red Faction: Guerrilla is an open-world game in which you literally bring down the establishment with a hammer and some remote explosives. It’s Demolition Simulator: Mars Edition, and its procedural destruction is some of the most purely satisfying gaming ever committed to code. There’s nothing better than setting up a nice big chain of explosives, hitting the trigger, and watching a whole line of chimney stacks crumble into the dirt.

But the true genius of Guerrilla’s destruction mechanic is how it instantly creates a template for your open-world game’s play. Like the Nemesis system, is provides that perfect blend of bespoke and dynamic action. Anywhere there’s a building, there’s something for the player to do, but the nuances of how that building is destroyed, and the consequences of that, is all down to the player’s own actions.

Only one other game has actually used this destruction mechanic, and that was the deeply inferior sequel to Guerrilla – Red Faction: Armageddon. I think it’s high-time we had another destruction-focussed open-world game. Can you imagine it with today’s tech? Oh my. I think I might have to lie down.

Boss Climbing – Shadow of the Colossus

There are few more cathartic accomplishments in gaming than bringing down a huge, seemingly insurmountable boss, but it always feels a bit odd to bring down a virtual titan by hacking at their feet for five minutes. Even the mighty Dark Souls suffers from this issue; you’re just too distracted by having your arse kicked inside out to notice.

What’s particularly bizarre is that this problem was solved nearly 15 years ago by the incredible Shadow of the Colossus. A game fundamentally about boss fights, SOTC realised the importance of making these fights feel dramatic, and that giving a Colossus the equivalent of a really bad stubbed toe wasn’t the way to achieve that.

Instead, the developers thought more logically about how one might overcome what is basically a living mountain. And in the absence of thousands of pounds of TNT, they came up with climbing. Each SOTC fight is thereby transformed into a living platform sequence, of hanging on for dear life as these gigantic creatures try to thrash you off, clawing ever higher and higher until you find a weak-point to sink your blade into.

The result is some of the most incredible encounters of any game, battles that do justice both to the size and majesty of those incredible creatures, and the effort required to take them down. You’d think after SOTC, boss fights would never be the same again. And you’d be wrong.

Only one other game I know of has deployed a similar mechanic, and that’s Dragon's Dogma – an underrated fantasy RPG that lets you grab and hold onto large enemies, hacking at them while they try to shake you off. It’s a lot rougher around the edges than SOTC, but it also conjures similar moments of majesty, and in slightly more dynamic way than SOTC does.

There is one game currently in development that has similar ambitions. Praey for the Gods (oh, that really is how they're spelling that? Well okaey. - ed.) is a spiritual successor to SOTC that sees you play a survivor in a wintery fantasy land, who seeks out and destroys giant creatures. Really, though, I think any game that involves taking down large enemies with swords should really feature a variant of this mechanic. Not only does it make a lot more sense than stabbing your opponent in the shins, it’s also a lot more enjoyable.

Logic-based inventory – Neo Scavenger

You may not have heard of Neo Scavenger, so let me give you a brief overview. Neo Scavenger is a turn-based, hex-based survival game in which you scavenge the ruins of the old world as you attempt to thrive in its harsh and strange wilderness. It’s as brutally challenging as it is stylistically lo-fi, but beneath those pixelly visuals are some fascinating ideas.

One of Neo Scavenger’s most important features is its incredible inventory system, which goes to great pains to simulate how a person could carry items in a survival situation. Basically, any item that you could theoretically put things into is simulated in the inventory, which expands and contracts depending on the items you have in your possession.

A simple example is that picking up a backpack will add greatly to your inventory space. But Neo Scavenger also uses the pockets of different kinds of clothes, and even lets you stuff items inside crisp packets and empty bottles, or roll up a plastic bag and put it in your pocket for later use. It is easily, easily, the best inventory system I have ever seen. It’s logical, it’s intuitive, and it’s a huge amount of fun to tinker with.

It’s not hugely surprising that more games haven’t picked up on Neo Scavenger’s inventory system. Neo Scavenger was a successful game relative to its budget, but it’s not one that many people know about. That said, its inventory does bear a curiously similar design to that of DayZ, so perhaps it is slightly more influential than things might seem. Regardless, more developers would do well to learn from the lessons of Neo Scavenger.

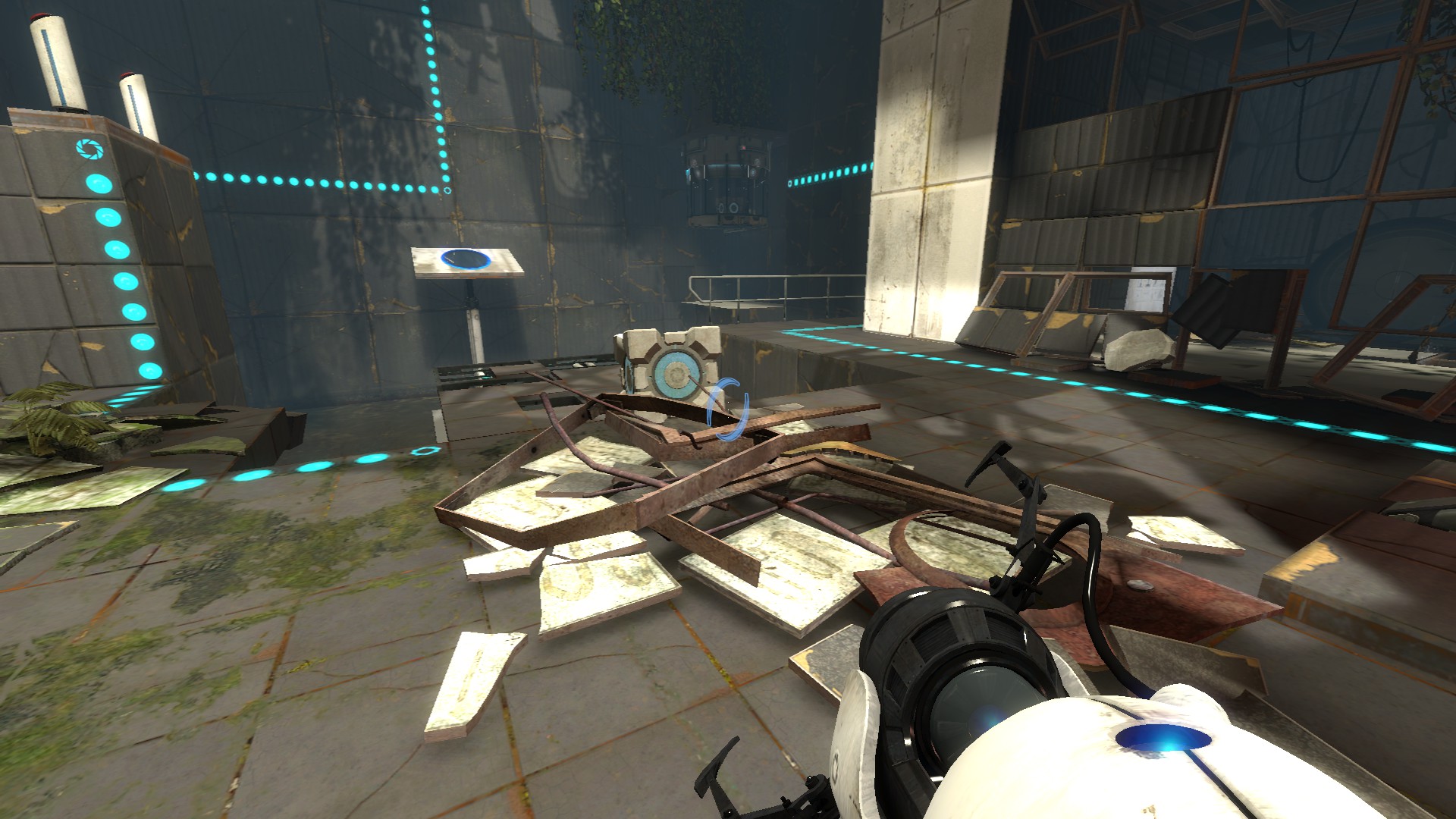

Portals – Portal

How? How are Portal and Portal 2 the only portal-related games around? How come nobody, not a single other developer, picked up Valve’s baton after 2007? Portal’s portals are one of the single biggest innovations in game design ever, the ability to transport items across any distance instantly, to connect any two points instantly, to use trajectory and momentum to propel any object.

It’s amazing to me that nobody else has borrowed this idea. You could make the most bog-standard third-person shooter infinitely more intriguing simply by adding a portal device. Okay, there was Prey (Pray? PRAEY? - ed.) , which in fact preceded Portal. But you couldn’t play with Prey’s portals; they simply existed.

To be honest, I’ve not much to add beyond an indistinct noise of bewilderment. Of all the mechanics on this list, this is the one that baffles me the most. You know what Portal is, and you know why it’s great, which makes it all the more bizarre that there aren’t more games like it. There must be some developer, somewhere, who played Portal and went, 'You know, what? This would be great if we added it to X?' I’d love to know if that was the case, and why, ultimately, they decided against pursuing it.

MSI MPG Velox 100R Chassis Review

October 14 2021 | 15:04

Want to comment? Please log in.