Price: £24.99

Developer: Storm in a Teacup

Publisher: Wired Productions

Platform(s): PC (PS4/Xbox One late 2019)

'BioShock meets Amnesia' is a handy way to summarise Close to the Sun. It isn’t as good as either of those games, admittedly, but it does have its moments. At times I was genuinely impressed by Storm in a Teacup’s high-minded narrative horror, particularly with regard to its amazing environment design. Ultimately, though, the whole experience doesn’t quite gel together, partly because of flaws in the storytelling, and partly because it feels decidedly unfinished.

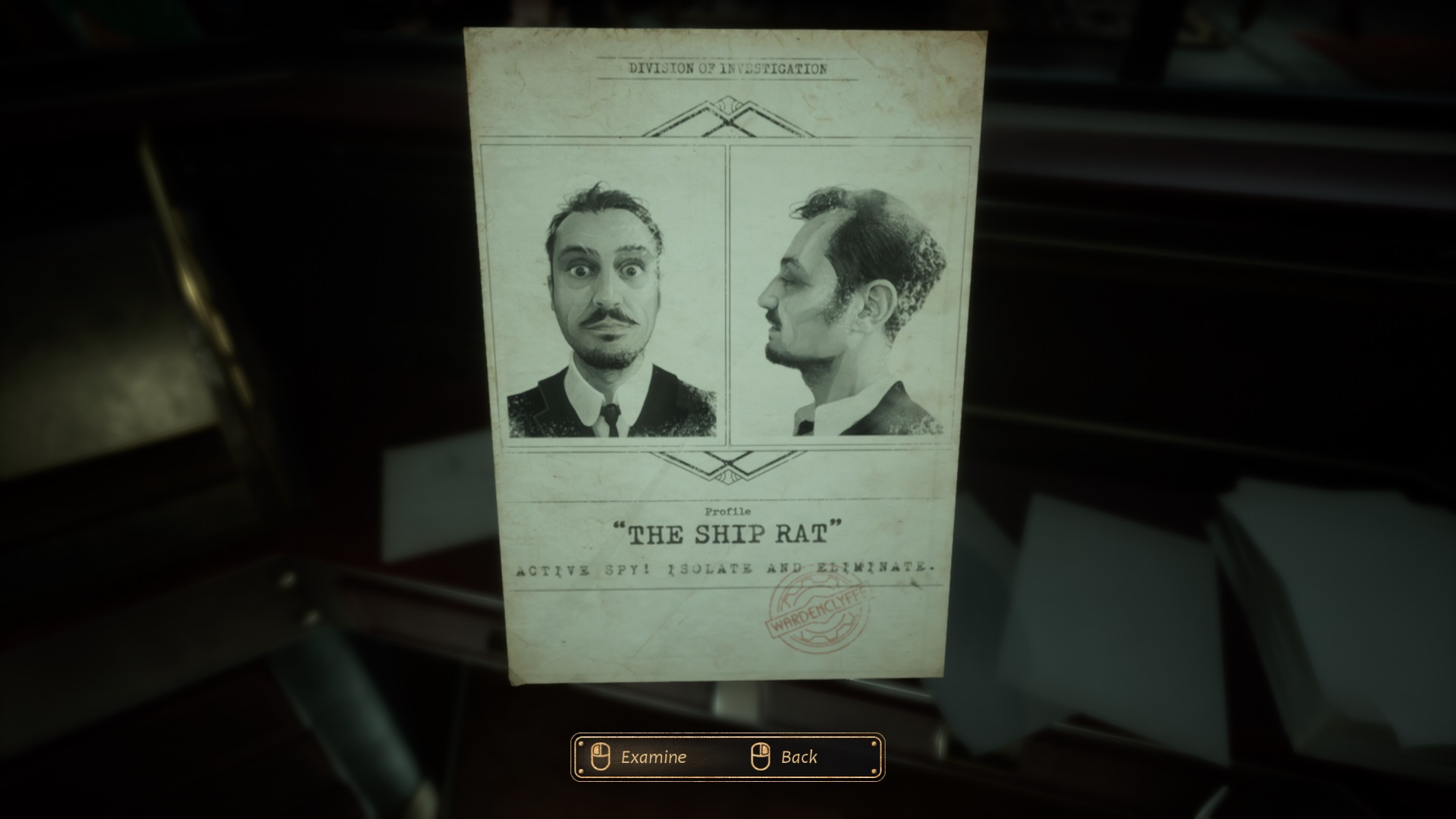

The year is 1897, and players assume the role of Rose, a journalist who receives a letter from her sister Ada urging her presence aboard the Helios – a gigantic scientific research vessel designed by Nikola Tesla. As in any story that involves isolating a group of scientists with some highly experimental technology, something has gone terribly wrong on the Helios, and it’s up to Rose to track down her sister and resolve the situation.

Comparisons with BioShock are impossible to avoid. Not only does Close to the Sun boast a nigh-identical art-style, its story is also about creating a utopian society where the greatest minds of the age are able to chase the farthest reaches of their imaginations, free from such paltry constraints as the law and scientific ethics. It even has a distinctly maritime theme; it just takes place on the sea rather than under it.

There are some key differences that we’ll get into, but right now I want to focus upon the most obvious point of comparison, the environment design. If you’re gonna come at the Art-Deco King, you best not miss, and Close to the Sun doesn’t so much hit its target as blow it out the water. I always thought BioShock looked good for its age, but Close to the Sun makes Irrational’s masterful FPS look positively ropey.

It's easily one of the best-looking games I’ve played this year, and bear in mind that includes games like Anthem and Metro Exodus. The decks of the Helios boast gleaming marble floors, lacquered wood panelling polished to a sheen, and glittering bronze statues in almost every room. Each of the game’s ten levels are breathtaking in their own way, from the detritus dockyard of the first level to the Helios’ unbelievably extravagant theatre.

It’s so good, in fact, that it almost works against Close to the Sun, as it makes you want to interact with these environment in a way the game simply doesn’t support. Close to the Sun very much belongs to the 'walking simulator' school of design, where much of your overall experience is passive. You walk around, you examine objects in the world, you listen to dialogue. But you never really feel like you can alter or manipulate the world in any meaningful sense. Your interactions are limited largely to opening doors and solving some very light puzzles.

It’s a shame, because you can build this kind of adventure without so aggressively preventing the player from environmental interaction, as games like Firewatch, Tacoma, and particularly Frictional’s SOMA demonstrate. There are times when the game leans this way too. The third chapter, which takes place in the residential area of the ship, is my favourite part of the game, because it lets you properly explore the area that you’re in, venturing into different crew cabins and thereby getting a sense of their lives.

There’s one cabin, for example, that belongs to the ship’s chess prodigy, and it’s strewn with half-finished chess games. These aren’t really interactive, but such elements nonetheless provide a sense of personality that involves you more directly in the space you’re exploring. Close to the Sun often feels like you’re passing through the game rather than playing it.

That said, it has a fantastic atmosphere, along with some nicely constructed scares. The best of these are environmental, a light sparking out, a door slamming shut, hinting at something rather than revealing it. Speaking of which, I’m less enthused by the 'chase' sequences (the game openly describes them as such, which makes them feel rather artificial).

There are a couple of reasons for this. Firstly, your character runs too slowly, which makes them feel slightly absurd. Secondly, the game likes to throw obstacles in your path, and the interactions to avoid these can be finicky. Several times I was forced to watch an overly long and overly grisly death animation because I didn’t press jump quickly enough.

My main issue with Close to the Sun, however, is with its storytelling. Initially I was intrigued by the plot, which deals with themes of time-travel, sisterhood, and some other intriguing concepts. Unfortunately, the game is badly let down by its dialogue. Close to the Sun allegedly takes place in 1897, but the characters talk like people from the 21st century, and as such conversations are laden with anachronistic turns of phrase. There’s one particularly dreadful moment when a German scientist named Aubrey utters the phrase 'my bad', and it pulled me so far out of the setting that I never settled back into it.

Since the game deals with time-travel, I did wonder whether this might be a deliberate choice, that perhaps somehow my character wasn’t actually from the 19th century. If that’s the case, however, the game never makes it clear. In fact, Close to the Sun fails to make a lot clear, ending in a very premature fashion that makes me think the developers either ran out of time/budget, or they’ve deliberately set it up for a sequel. Regardless, it doesn’t offer anything like sufficient payoff as an individual entity, and I was left with numerous unanswered questions.

I should stress that, despite picking over its bones rather thoroughly, I did enjoy Close to the Sun. But it could have executed a lot of what it attempts better, certainly from a storytelling perspective. Nevertheless, I think Storm in a Teacup is a developer to watch. Out-rapturing Rapture is no mean feat, and I’m keen to see what the studio has planned for the future.

MSI MPG Velox 100R Chassis Review

October 14 2021 | 15:04

Want to comment? Please log in.